Contents

ANSI escape codes

Most of the time, we think of a computer terminal as a place to output text. We generate logs and print output from programs to the terminal, and interact with the shell by typing lines in and getting lines out. When teletype terminals first came to be, text input/output was indeed all it did. It was called a “terminal” because terminals were separate, independent devices at the terminal ends of computers, connected by serial connections, receiving commands from a mainframe computer stored somewhere else in a facility. As terminals became digitized, more powerful, and more integrated into smaller computers, we started asking more out of terminals.

Today, terminals can run rich, interactive programs like IDEs, work with mouse pointers, and even display images. But few things were pristinely designed and executed from the get-go in the evolution of the venerable terminal from a simple text input/output device to the rich interactive console we have today. Most of the capabilities of modern terminal emulators, like interactive graphics and mouse events, have been grafted onto the existing modes of operation for text terminals.

There are two main ways modern terminals can provide rich interactive functionality: through ANSI escape sequences and ioctl or similar system interfaces. ioctl is used for bi-directional communication between the terminal and the operating system, for things like window sizing and mouse control. I won’t delve into that today. Instead, let’s talk about ANSI escape sequences, which are used for color output and cursor movement.

As terminals were just getting the ability to be more interactive and have color output, each terminal manufacturer created their own standard for how the terminal should receive these rich messages from the computer at the other end of the line. Eventually, the industry (via ANSI, the American National Standards Institute) standardized around escape codes from the popular VT100 terminal. Today’s terminals use these same escape codes, and today’s software terminals emulate the VT100 as a legacy of backwards compatibility.

How do they work?

ANSI escape codes are an in-band signaling mechanism, meaning the commands are sent as a part of the normal stream of text being output to the terminal. To issue a command to a terminal output device, wherever appropriate, we can insert a sequence of characters starting with ^[ (the ASCII Escape character, byte 0x1b). The terminal then accepts these characters and interprets them as ANSI escape codes, instead of displaying them to the user.

For example, to print Hello, World! we’d normally print the string 'Hello, World!'. To print it as red text, we precede the string with the escape sequence ^[[0;31m. If we print '\x1b[0;31mHello, World!' to an ANSI compliant terminal, we’ll get Hello, World! in red.

Similar commands exist for other types of command and operations like moving the cursor, or clearing the screen.

As another example, the clear utility to clear your terminal doesn’t do anything fancy to talk to the system or terminal. clear really just outputs a string of two ANSI escape sequences:

$ clear | xxd -

00000000: 1b5b 481b 5b4a .[H.[J

Here, we can see clear outputs six bytes, which xxd has rather unhelpfully grouped into sets of 2. But we can interpret them correctly:

1b 5b 48is^[[H, which moves the cursor to the “home” position, which is line 0, column 0 – the top left corner of the terminal1b 5b 4ais^[[J, which clears the terminal screen from the cursor-down. Since the cursor is now at 0, 0, this clears the entire screen.

The ansi library

As an in-band signaling mechanism, ANSI escape codes are easy to use in every programming language, but its syntax is pretty unergonomic. It involves memorizing strange numbers that you wouldn’t want in your business logic code. So it’s a good candidate for an easy, simple library.

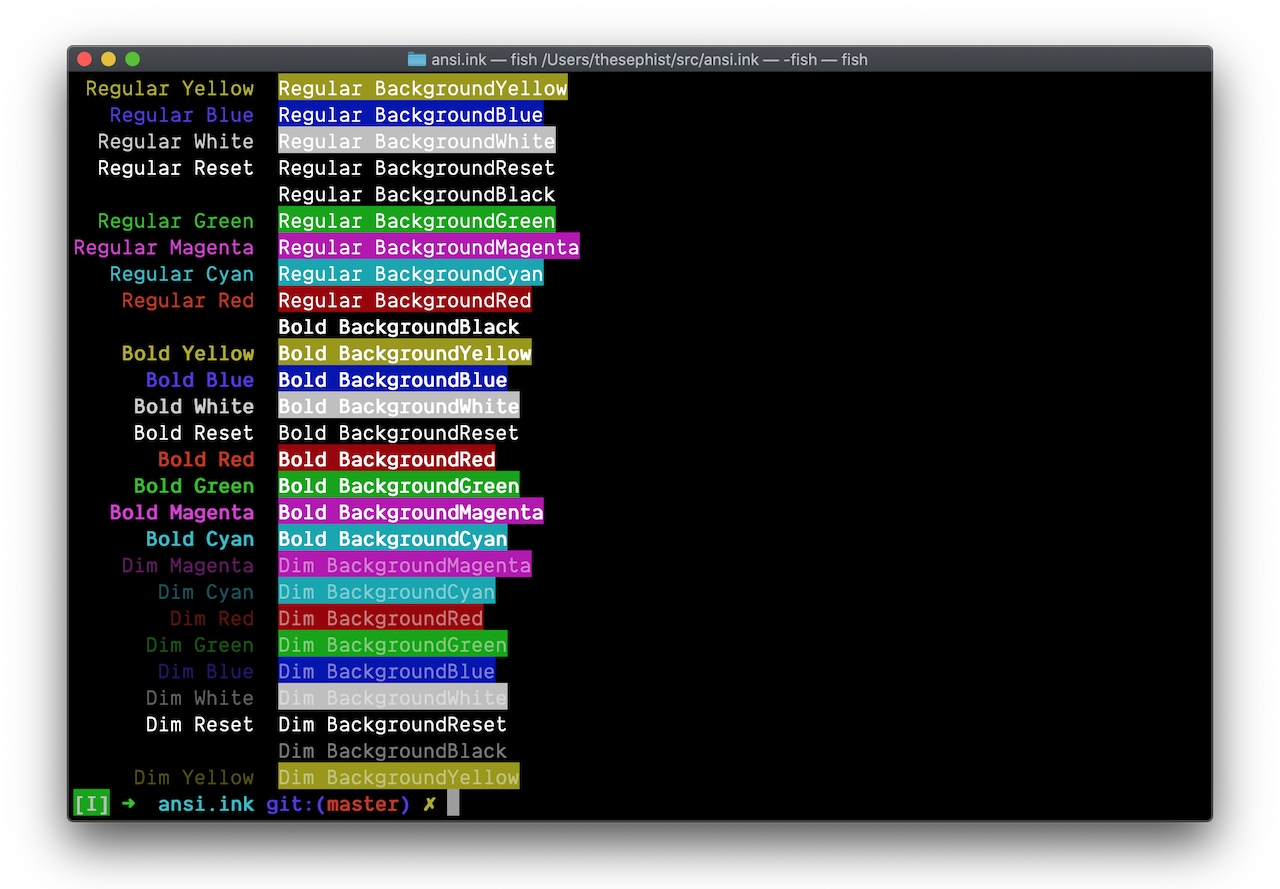

ansi.ink is an Ink library to handle a small set of common escape sequences, including basic cursor movements, clearing screens and lines, and color output. You can find the documentation in the GitHub README.

The core of the ansi library is just around 50 lines – just a convenience wrapper around escape codes and little else.

ansi also happens to be the first library for the Ink language that’s out-of-tree (maintained outside of the main thesephist/ink source tree.) Ink itself is pretty slow-moving these days, so I think this won’t be an issue.

← Binary search for rational approximations of irrational numbers