Contents

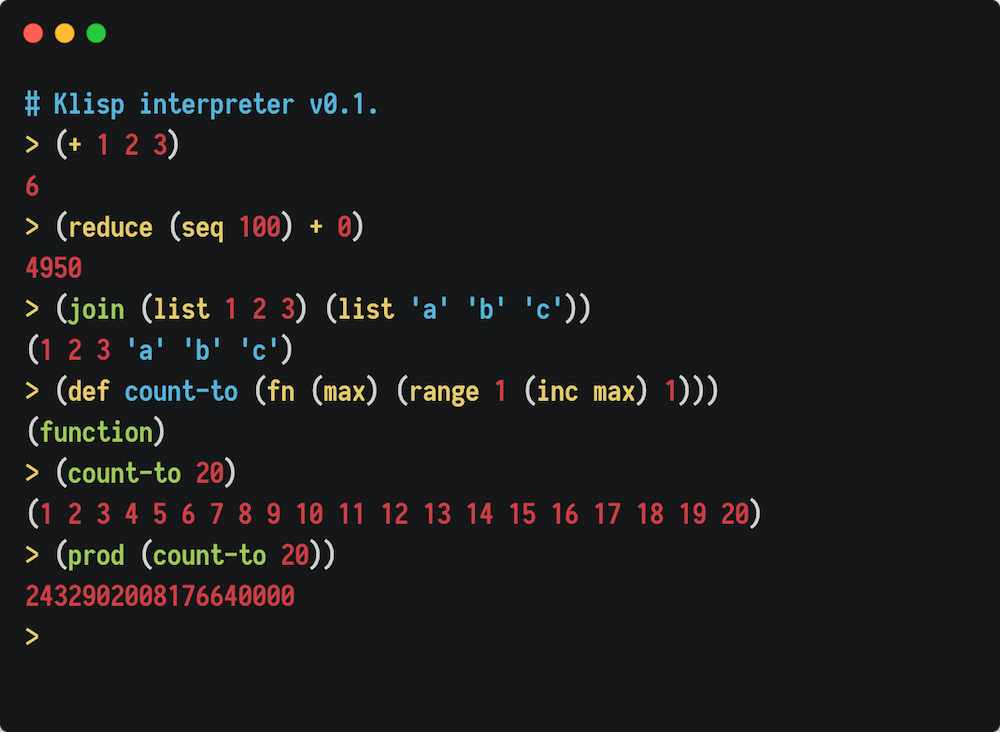

Klisp (named after inK LISP) is a very minimal Lisp environment with a core written in about 200 lines of Ink. In addition to the interpreter itself, Klisp also includes an interactive repl and a small standard library that makes operations on lists and Klisp values easy and idiomatic.

Under the hood, Klisp implements a minimal core Lisp dialect with six special forms: quote, do, def, if, fn, and macro. From these building blocks, Klisp builds up a richer vocabulary of functions and macros for working with lists and functions to build interesting programs. Klisp borrows at a high level from Scheme and Clojure, but is its own dialect of Lisp.

You can read more about the Klisp project in the GitHub repository. The rest of this post explores how Klisp is currently implemented, in both the Ink-based core and the standard library.

Implementing Klisp

The core of Klisp is implemented purely in Ink in a single source file, in three separate functions, read, eval, and print. In the classic Lisp tradition, read parses a string input into a Lisp data structure (of linked list nodes called L in the source code), eval evaluates a list as a Klisp program, and print transforms Klisp lists back into strings – the inverse of read.

Before diving into the implementations of these core routines, we need to decide how to represent Klisp values in an Ink program.

Representing Klisp values

Ink is, semantically, a Lisp. Although it has a unique syntax and therefore can’t take advantage of the benefits of homoiconicity, Ink programs are composed of lexically bound values and small functions working on other primitive values, with functions as first-class values and tail recursion as the preferred looping paradigm. Given this fact, I chose to represent most Klisp values as raw Ink values:

- Klisp strings are Ink strings (mutable byte arrays)

- Klisp numbers are Ink numbers (64-bit floats)

- The null value in Klisp

()is the same in Ink

There are three values that require more consideration: lists, functions, and symbols. The only composite type in Klisp is the pair, a cons cell, used to build up lists. Klisp represents a cons cell with a length-2 list in Ink: [_, _]. Klisp also has two kinds of function-like values: functions and macros. Klisp stores these as length-3 Ink lists, [_, _, _], with the first slot reporting whether a function is a macro, the second containing the runnable function, and the third disambiguating this value from list nodes (but containing no useful value). For example, the car built-in function is represented as the Ink list

[

false `` not a macro

L => L.'0'.0 `` the function itself

_ `` empty value

]

Klisp has a symbol type, sometimes called the “atom” type, whose equivalent does not exist in Ink. A symbol is an atomic name that a program treats as a special value, and binds to a value in a scope. Because symbols are named, Klisp implements a symbol as a string prefixed with the null byte \0. This ensures that symbols will not conflict with strings as values, but are still efficient to move around the interpreter, and ca be used as keys to the map backing each variable scope.

With this set of types, all Klisp values are representable unambiguously as Ink values in the interpreter.

The read function

The read function transforms a string of input to a Klisp list data structure containing the parsed code. Unlike most parsers, the reader in Klisp does not contain a separate tokenizing step. Instead, read tokenizes as it goes, parsing the entire Klisp program in a single pass. This is possible because of the language’s S-expression syntax.

The reader function parses all S-expressions in the given input sequentially, and wraps the program in a single do block to create one eval-able list of expressions, to pass it off to eval.

The eval function

eval is the heart of the interpreter, and implements evaluation rules for the six special forms in the language.

The evaluator is implemented primarily as a big nested match expression, jumping to the right match branch for each kind of S-expression node. When a special form is found, it’s processed according to language rules. If no special form is found, the evaluator asks whether the head of the list is a function or a macro, and runs it. Literal values are passed straight through the evaluator, and symbols are looked up in the local environment (variable scope).

A scope is implemented with a simple Ink dictionary (object). When child scopes are created in a program, the child scope gets assigned a special value with the key -env that points back to the parent scope’s dictionary. This name doesn’t conflict with any variable names, because variable names (symbols) are prefixed with the null byte. In this way, lexical scope trees can be simply represented as a tree of dictionaries with pointers to parent scopes.

The Klisp evaluator is an environment-passing interpreter. Each invocation to eval also passes the environment dictionary in which the given Klisp code should be evaluated. Because Ink is tail-call optimized, equivalent expressions in Klisp are also tail call optimized by default.

Although not a part of the evaluator, the default environment is worth mentioning here. When eval is first invoked by the Klisp tool, a default, top-level environment is passed in. This default environment contains all the built-in values in Klisp, like true / false, list manipulation functions, and arithmetic operators. The default environment is exported as Env from klisp.ink.

The print function

As the complement to the read function, print takes a Klisp program as data and prints it back as S-expressions. Like eval, print is a single nested match expression, recursively invoking itself for lists and pretty-printing literal values as Ink values.

print is the shortest function of the triplet, and by far the simplest.

A taste of Klisp

In many ways, Klisp is just a syntactically minimal Lisp. You won’t find reader macros or complex data types in Klisp, but the basic building blocks are all present. One simple Klisp program here defines a function and invokes it on a number.

; square is a function x -> x^2

(defn square (x)

(* x x))

(square 11) ; => 121

Here, defn is a core library macro that expands the first few lines to:

; square is a function x -> x^2

(def square

(fn (x) (* x x)))

In either case, we bind the variable square in the top-level scope to a function returning a number multiplied with itself, then call that function on 11.

The core data structure of Klisp is a list, which is a recursive sequence of S-expressions. The Klisp core library offers many common functions that operate on lists.

(def nums (range 0 10 1))

; => (0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9)

(map nums inc) ; "inc" increments a number

; => (1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10)

(def even-nums

(filter nums even?)) ; "even?" defined elsewhere

; => (2 4 6 8 10)

(size even-nums) ; => 5

(nth even-nums 2) ; => 6

(sum even-nums)

; => 30

Klisp also allows for macros, and the core library offers a few useful macros for declarative control flow. cond and match are two such good examples. cond lets you concisely express a list of if-else cases in a single block, and a match block implements a switch-case. Here’s a simple FizzBuzz implementation using the cond macro.

(defn fizzbuzz (n)

; for each natural number through n,

; evaluate the following function:

(each (nat n)

(fn (i)

(cond

((divisible? i 15)

(println 'FizzBuzz'))

((divisible? i 3)

(println 'Fizz'))

((divisible? i 5)

(println 'Buzz'))

(true (println i))))))

Much more on Klisp as a programming language can be found on the GitHub readme, and in the core library implementation in lib/klisp.klisp.

Next up

Klisp is a pedagogical project, and isn’t (at the moment) intended to be used to build anything serious or practical beyond learning to write programs in a Lisp. This is in part because the language is still shifting somewhat underneath, but also because Klisp is still quite slow and unsafe. The interpreter written in Ink does not handle most errors in incorrect programs well, and is very slow partly due to the host language, and partly because of a lack of efficient data structures like vectors. These are tradeoffs I chose in the initial implementation with the goal of learning in mind.

However, I enjoy writing programs in Klisp, and I hope to continue to add to it. Lisps tend be able to grow organically over time much better than most other languages, and I enjoy coming back to Klisp to write small programs and add a function or two to the core library once in a while. In the process I also hope to address the two tradeoffs I highlighted above – error handling and performance. I believe performance may be improved by using a faster Ink interpreter under the hood like Schrift, and with the additional performance headroom, better error handling logic may also come.

I’m also thinking about using Klisp in other potentially interesting software projects going forward. The Nightvale project, for example, is written entirely in Ink and uses Klisp as the programming language of choice in the client.

I’ve really enjoyed exploring Lisps so far, and Klisp is the lastest in that journey that I hope will take me much farther, for much longer.

← Weighing software abstractions to design better programs

Nightvale: an interactive, literate programming notebook built on Ink →