Contents

The lambda calculus is a formal model of computation, a mathematically rigorous way of thinking about what computers do. Unlike the other popular theoretical model, the Turing machine, the lambda calculus describes all computation in terms of pure functions, and functions acting on other functions.

Lambda calculus is a useful model because of its inherent simplicity. It allows computer theoreticians to model more complex computation using simpler parts that lend themselves nicely to study. The lambda calculus also happens to be a generally useful model of computation for functional programming languages, like Lisps and Haskell.

While the lambda calculus is a theoretical model, we can also build real, executable implementations of the lambda calculus using programming languages with first-class functions, by modeling all computation using functions in the programming language.

Through this post, we’ll pick apart the basic building blocks of programs we’re normally familiar with, like numbers and conditionals, using the primitives of the lambda calculus. We’ll end with an implementation of the factorial function, implemented fully within our Ink-based mini lambda calculus implementation.

You can also find the full source file of everything covered in this post in the lambda.ink project, including a thoroughly commented implementation.

The world of (pure) functions

For simplicity, we’ll only consider functions that take one input, and return one output value. Some examples of such functions are

`` identity

x => x

`` doubles the input

x => 2 * x

`` square

x => x * x

Functions can also take other functions as input, and operate on them. For example, a function may take a function and invoke it with a constant

`` calls a given function with 2

f => f(2)

Currying

A more interesting thing a function can do is to return another function. In other words, a function might be defined as

f := x => (y => x + y)

f(2)(3) `` => 5

This function f takes x, and returns another function that takes y, and returns the sum x + y. We can call it once to get a function, and then call that returned function again to get a result. In effect, this is the same as a function that takes two arguments, like (x, y) => x + y. But here, we can see that two-argument functions are really just syntactic sugar over the single-argument function!

f := x => y => x + y

f(2)(3) `` => 5

`` ^^ is the same as vv

f := (x, y) => x + y

f(2, 3) `` => 5

This process of rewriting a multi-argument function as a bunch of single-argument functions that return other single-argument functions is called currying, named after the computer scientist Haskell Curry.

We can curry a function as many times as we’d like, to produce multi-argument functions like

sumWithTen := a => b => c => a + b + c + 10

sumWithTen(1)(2)(3) `` => 16

It’s helpful to recognize that a function written in the form _ => _ => ... => _ is just another way of writing multi-argument functions, because it shows up everywhere in the lambda calculus. With this in mind, we’re ready to start defining the basic building blocks of programs in the lambda calculus.

A note on notation

In the academic literature, computer scientists use a single mathematically defined notation for representing functions in the lambda calculus, rather than emulating any particular programming language. While we won’t use it much in this post, it’s useful to know when reading outside literature, so I’ll summarize it here.

The notation has two rules:

-

We define a function that takes variable \( x \) by using the lambda (\( \lambda \)) symbol.

x => x + 3is written \( \lambda x . x + 3 \).We can also write curried, multi-argument functions this way.

a => b => a + bis written \( \lambda a . \lambda b . a + b \) using two different lambda “bindings”. Sometimes you’ll also see this abbreviated to \( \lambda a b . a + b \), but they mean the same thing. -

We apply a function \( f \) on a variable \( x \) by simply writing them next to each other, like \( f \ x \).

We can define a function and immediately invoke it on a value. For example, we can write

$$ (\lambda x . 2x) \ 10 = 20 $$ $$ (\lambda abc . ab + c) \ 10 \ 20 \ 30 = 230 $$

These would be written equivalently in Ink as functions

(x => 2 * x)(10) = 20 ((a, b, c) => a*b + c) (10, 20, 30) = 230

We’ll mostly stick to more familiar (to us programmers) notations in this post, but as we reference ideas from the rest of the field, being able to read the lambda notation will come in handy.

Church numerals

To write programs in the lambda calculus, we first need to model some data that our functions can act on. To keep it simple, here we’ll just define the natural numbers. But we can’t just use the built-in numbers 1, 2, 3 ... because we can only use functions in the lambda calculus. We need a way to represent the natural numbers using pure functions.

The Church encoding is the most popular way to encode numbers in functions. It gives the following conversion rule:

A number \( n \) is encoded as a function that takes another function

fand an argumentx, and invokesf\( n \) times onx.

Let’s define some numbers using this rule. A zero is simple: it’s a function that takes an f and some argument x, but doesn’t ever call f (or, calls f zero times, which is the same thing).

Zero := f => x => x

We represent the number 1 as a function that calls the given function exactly once on x, and so on…

One := f => x => f(x)

Two := f => x => f(f(x))

Three := f => x => f(f(f(x)))

How do we use Church numerals? One thing we might want to do is to convert these representations of numbers into the numbers we’re familiar with. We can write a little helper function to do that, which looks like this

`` convert Church numerals to Ink numbers

toNumber := c => c(n => n + 1)(0)

toNumber(One) `` => 1

toNumber(Three) `` => 3

toNumber converts Church numerals (which are functions) to Ink numbers by calling each Church numeral with f set to an “add one” function and the starting point x as zero. This means, for example, our definition of Three will call the “add one” function 3 times on 0, giving us the number 3.

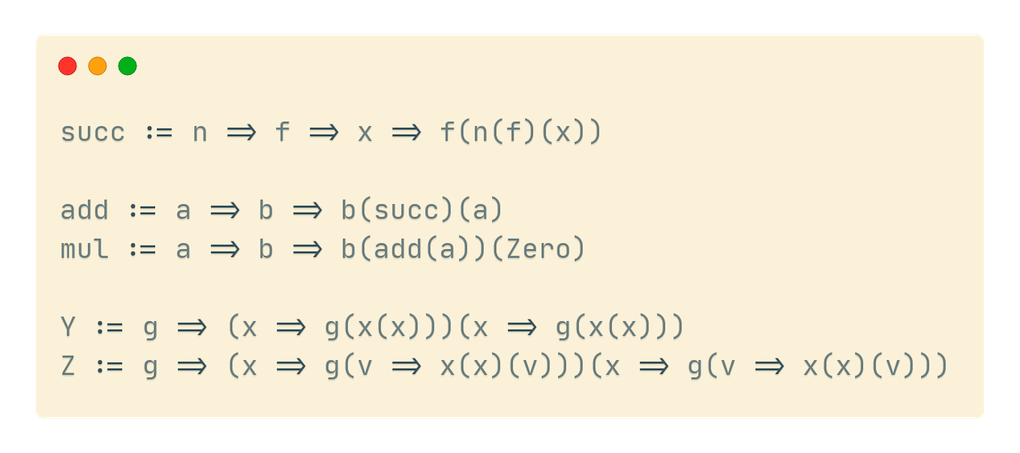

To do anything useful with Church numerals, we need to define a few arithmetic functions, starting with a “successor” function, conventionally spelled succ, that increments a Church numeral. In other words, succ(One) = Two and succ(Two) = Three. The function succ can be written

`` Takes N and returns N + 1

succ := n => f => x => f(n(f)(x))

The succ function takes a Church number n (a function taking f, x) and gives us a function that calls f on x one more time than the function given to it.

The fact that the definition above actually does this might not be obvious at first. But if you sit with it and play with some examples or code, it’ll click.

Using succ, we can define basic arithmetic. add, for example, is a function taking two numbers a and b and calling succ on a, b times. We can use this pattern to define multiplication (adding a number n times) and powers (multiplying a number n times).

` We can define arithmetic over Church numerals.

To add A and B, we add 1 to A, B times.

In other words, we apply succ to A, B times. `

add := a => b => b(succ)(a)

` A times B is A added to zero B times. `

mul := a => b => b(add(a))(Zero)

` A^B is 1 multiplied by A B times. `

pow := a => b => b(mul(a))(One)

Though we won’t go into much detail, there is a complement to succ called pred, which is a “subtract one” function. In other words, pred(Two) = One. Using pred, we can define subtraction, division, and logarithms. It turns out the implementation of pred is quite a bit more complex than succ. Our implementation counts up from zero to find the number whose succ is the given number, but don’t stress if you don’t grok this function yet.

`` zero? uses booleans, defined later in the post

zero? := n => n(_ => False)(True)

pred := n => n (g => k => zero?(g(One))(k)(succ(g(k)))) (_ => Zero) (Zero)

` subtraction is just repeated predecession `

sub := a => b => b(pred)(a)

To recap, with the Church encoding of numbers, we’ve found a way to represent all non-negative integers as pure functions, or “lambdas”. We’ve also found ways to do basic arithmetic on that representation of numbers, built on the basic operation of incrementing numbers up and down by 1.

We have invented numbers. Let’s move on to booleans.

Booleans

Booleans in the lambda calculus are encoded as “selector functions” that choose between two arguments. Given two arguments, the lambda calculus representation of “true” will pick the first choice, and “false” will pick the second choice. Think of true and false values as an if-else check over two choices.

True := x => y => x

False := x => y => y

We can write a toBool function that converts our lambda calculus representation of a boolean into a normal Ink boolean value as follows. The boolean, which is a selector function, will pick true if it’s True, and pick false if it’s False.

toBool := c => c(true)(false)

Using these representation of booleans as functions, we can define some boolean operators, like not, and, and or. These operations aren’t immediately obvious, so sit with them for a bit and think about how the descriptions in comments are true about each operator.

` <not> x simply flips the given value's choice. `

not := x => x(False)(True)

` A <and> B returns B if A is true, and false if A is false. `

and := a => b => a(b)(False)

` A <or> B returns true if A is true, and B if A is false. `

or := a => b => a(True)(b)

Using these functions on boolean values, we can describe any boolean predicate.

We can now break down and understand a function we saw earlier in the definition of pred called zero?. zero? returns whether the given argument is Zero. We can’t compare the argument directly to Zero, because they might be two different functions that do the same thing, and are thus both technically Church-encoded “zero” values.

Instead, our definition of zero? takes a Church-encoded number, and calls it with f set to an always-false function, and x set to True. If f is called a non-zero time on x, we get False. Otherwise, we get True, like we’d expect.

zero? := n => n(_ => False)(True)

We have now invented booleans in the lambda calculus.

Recursion and fixed-point combinators

To reach our goal of implementing a factorial function, we need numbers and booleans. However, we need one more missing piece: recursion. The basic lambda calculus doesn’t support recursive definitions. In other words, we can’t reference a function within its own definition, which we need to do to define the factorial function.

To express recursion, we’ll need the help of fixed-point combinators.

A fixed point of some function is a point where the input and output to the function match. In other words, if \( x \) is a fixed point of \( f \), then \( x = f(x) \). For example, for the function \( f(x) = x^2 \), the number 1 is a fixed point because \( f(1) = 1^2 = 1 \). \( 0 \) is another fixed point of this function.

A combinator in the lambda calculus is simply a function without any un-bound (or “free”) variables. x => y => x + y has both variables “bound” to arguments, while x => x + y has a “free” y variable, since it was never defined as an argument. For our purposes here, you can think of a “combinator” intuitively as a “completely defined function”.

A fixed-point combinator is a combinator (a function) that takes another function, say g, and returns a fixed point of the given function. In other words, a fixed-point combinator \( \mathrm{fix} \) is defined so that

$$ \mathrm{fix} \ g = g(\mathrm{fix} \ g) $$

This is a little mind-bending, and the definition isn’t very intuitive. Let’s see why we need a combinator like this to define recursion.

When we define a recursive function like the factorial, we need to reference the function itself in its body. In pseudocode, this looks like

def factorial(x):

if x = 0:

return 1

else:

return x * factorial(x)

The rules of the lambda calculus technically don’t allow us to write such a function, because lambda calculus doesn’t support named functions like factorial here. We can only give names to arguments, not functions defined in some “global scope”.

Given this limitation, we might try to re-write a factorial like this:

def fakeFactorial(realFactorial):

return function(x):

if x = 0:

return 1

else:

return x * realFactorial(x)

Defined this way, if we can call fakeFactorial with its own return value as its argument, we’ll evaluate our factorial function. A fixed-point combinator lets us call a function with its return value as its own argument in an infinite loop, as we can see from its definition if we say \( g = \mathrm{fakeFactorial} \).

$$ \mathrm{fix} \ g = g(\mathrm{fix} \ g) = g(g(\mathrm{fix} \ g)) = \cdots $$

Let’s explore a few common fixed-point combinators we can use.

The Y combinator

The Y combinator is the best-known fixed-point combinator in the lambda calculus. In the conventional notation, it’s defined as

$$ \mathrm{Y} = \lambda f . (\lambda x . f ( x \ x )) (\lambda x . f ( x \ x )) $$

In our more familiar programming notation, the Y combinator is

Y := g => (x => g(x(x)))(x => g(x(x)))

We can see that this Y combinator satisfies our definition if we expand it out.

Y(g) = (x => g(x(x)))(x => g(x(x))) -> definition of Y(g)

= g(x => g(x(x)))(x => g(x(x))) -> apply the function (x => g(x(x)))

to its argument (x => g(x(x)))

= g(Y(g)) -> by definition of Y(g)

Now, we should be able to define a fakeFactorial in the lambda calculus, and pass it to Y to create a recursive factorial function:

fakeFactorial := realFactorial => n => zero?(n) (_ => One) (_ => mul(n)(realFactorial(pred(n)))) ()

factorial := Y(fakeFactorial)

factorial(Three) `` => we should expect Six

If we run this program, though, we’ll quickly run into an infinite loop that never terminates. This is because Ink, like most programming languages, is eagerly evaluated, which means we compute arguments to functions regardless of whether the function needs them. While the Y combinator as defined works in the boundless world of mathematics, it turns out the assumption of infinite space and memory doesn’t work for conventional programming languages.

But not all hope is lost.

The Z combinator

The Z combinator is another fixed-point combinator, specifically designed to work within the constraints of eagerly evaluated languages. It’s defined as

$$ \mathrm{Z} = \lambda f . (\lambda x . f(\lambda v . x x v)) (\lambda x . f(\lambda v . x x v)) $$

In the notation of code, this Z combinator is

Z := g => (x => g(v => x(x)(v)))(x => g(v => x(x)(v)))

Although we won’t prove the fixed-pointed-ness of the Z combinator here, you’re welcome to try it at home if you feel so inspired by the Y combinator example earlier in this section.

The Z combinator emulates laziness in eagerly evaluated environments by wrapping the parts that need to be lazy in something like closures. With this Z combinator, we’re ready to write our factorial function in the lambda calculus.

The factorial

First, let’s write our equivalent of the fakeFactorial function, defined without recursion.

fakeFactorial := fact => n =>

zero?(n) (_ => One) (_ => mul(n)(fact(pred(n)))) ()

Then we have our Z fixed-point combinator

Z := g => (x => g(v => x(x)(v)))(x => g(v => x(x)(v)))

To test it, we can define our recursive factorial using the Z combinator and call it on a few values

factorial := Z(fakeFactorial)

toNumber(factorial(Zero)) `` => 1

toNumber(factorial(One)) `` => 1

toNumber(factorial(Two)) `` => 2

toNumber(factorial(Three)) `` => 6

toNumber(factorial(Five)) `` => 120

There we have it! A complete implementation of the factorial function in pure lambda calculus, with numbers and booleans represented as pure functions, and recursion achieved using a fixed-point combinator.

Further reading

If you’re interested in understanding these topics more deeply or reading further into the lambda calculus and its many cousins like the typed lambda calculus or the SKI combinator calculus, here are some links I found useful in my investigations:

- The Wikipedia entries on the lambda calculus, fixed-point combinators, and the Y combinator are useful starting points

- An in depth guide to implementing fixed-point combinators in real programs

- Implementing the Y and Z combinators in JavaScript

And lastly, you can find a complete, thoroughly commented implementation of everything covered in this blog in a runnable Ink program at github.com/thesephist/lambda.

← BMP: the simple, underappreciated image file format

Taming infinities: adding tail call elimination to Ink runtimes →