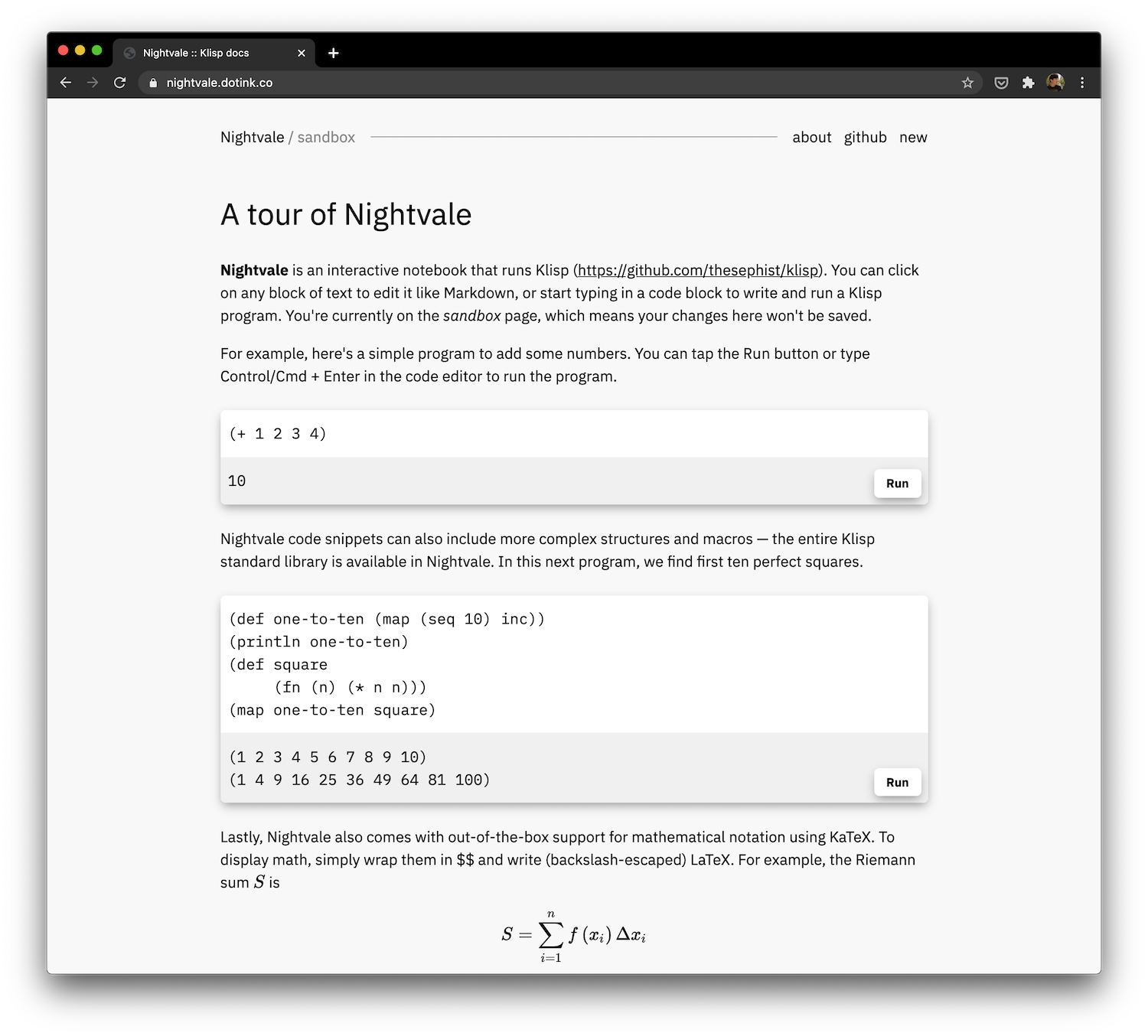

Building on my progress and positive experience with Klisp, I recently created Nightvale, an interactive notebook in the browser for literate programming and communicating computational ideas using Klisp code. On Nightvale, I can create docs that combine rich (Markdown-esque) text, mathematical notation, and runnable Klisp code to explain ideas. Nightvale is written entirely in Ink on the backend, and uses my Torus UI rendering library on the client.

The name Nightvale comes from the podcast Welcome to Night Vale, but besides the fact that the name sounded good to my ears, the two have no connection.

I think there’s so much more to do in building great computational notebooks, both on top of Nightvale and elsewhere in the marketplace, and want to share some of those thoughts – as well as how Nightvale itself works – here.

Literate programming notebooks

If code comments provide context for source code in software, literate programming is about placing software entirely in context. Many times, it’s valuable to think about and study software in context of a larger narrative, than simply study an implementation independently. Context can provide additional reasoning behind design decisions and tradeoffs, but more importantly, software in context can be a great explanatory tool to teach new ideas in mathematics and computation. Programming notebooks like Nightvale, Jupyter, and Observable all give us ways to explain ideas and provide interactive examples of playing with those ideas in code right next to it. As both a writer and a software enthusiast, literate programming notebooks feel like the ultimate educational and creative medium.

There’s a long and illustrious history of research and experiments into building interactive, literate programming environments. While Nightvale doesn’t push any boundaries, it takes inspiration from prior art.

Observable notebooks and Jupyter notebooks are the two most influential and conceptually rich of these inspirations. Though we can write full, useful programs in both Observable and Jupyter notebooks, the primary purpose of these computational notebooks is to communicate or explain. There is a lot of power in good explanations. Good explanations are how good ideas replicate across a community. The better tools we have to share great explanations, the more efficiently we can build and share good ideas. Nightvale isn’t as feature rich as either of these products, but the vision is the same – enable me to write good, natural, interactive explanations of mathematical, quantitative, and computational ideas.

Nightvale is also closely related to the idea of repls and other richer development environments. I’ve been thinking a lot about Lisp repls while developing Nightvale, and taking conceptual hints from repls in Clojure and Julia. In some ways, each code block in Nightvale is a small repl, providing quick feedback for small, bite-sized programs.

Lastly, mathematical notation is a key part of Nightvale. Natural language, programming languages, and mathematical notation all bring different kinds of abstraction capabilities at different levels of precision, and I think having the full expressive gamut of tools available in a single document lets the author choose the best tool for explaining a given idea.

How Nightvale works

Nightvale uses a client-server design to allow for writing programmable documents. The server, written in Ink, incorporates a limited variant of the Klisp interpreter where the evaluator has a lower maximum recursion limit than normal, to prevent infinite loops and excessive CPU consumption by untrusted code. When a document loads in Nightvale, any embedded programs are sent to the evaluation service in the backend over simple HTTP APIs to retrieve results, which is displayed in the document. At the moment, the server keeps no state in between evaluations, so each code block must be a standalone Klisp program. This lets the evaluation service be completely stateless, which makes Nightvale simple.

The client side of Nightvale is written as a single-page Torus application. Each Nightvale doc is stored as a list of blocks of text. Each block is either a rich text block, rendered with Markus (a Markdown-esque parsing library for Torus), or a code block, rendered as an in-document runnable code editor. Within rich text blocks, KaTeX is used to render mathematical notation.

On the backend, the Ink-based server uses an http server and routing library I initially wrote for Polyx. Documents are saved to disk as JSON blobs under a “database” directory on the server, which is primitive, but works well enough for my limited use cases.

The possibilities are vast

There’s a lot of room for Nightvale to grow into a beautiful and functional tool for taking notes and sharing explanations, and what’s there today is an MVP. Inspired by existing notebooks and repls, I want to add more options for visualizing program output (into graphs, tables, and charts), improve the code editor to be a properly ergonomic Lisp editor, and maybe even allow programs to provide interactive UI elements as output, as in Observable’s notebooks.

Most importantly, I think Nightvale is just a great medium for writing hybrid documents about math and programming, and I look forward to sharing my ideas through it.

← Klisp: a Lisp in about 200 lines of Ink

A retrospective on toy programming language design mistakes →