This blog post originally appears on the Oak Blog. It’s been copied here, because when this blog went up, the Oak blog wasn’t quite ready for primetime. For syntax highlighted Oak code and other information about the Oak language, you can read the same blog post there.

I made a couple of much-needed optimizations to the JavaScript code generator in oak build this week, focused on runtime performance and generated code size. As usual for these focused optimizations, I tried to run some benchmarks and comparisons to validate the changes. This is a summary of exactly what changes I made, and how they improved the compiler.

Reducing code size

The first round of changes were focused on reducing generated code size. Compiling Oak into JavaScript already results in quite large files, compared to their original source counterparts. This is because the compilation to JavaScript wraps Oak constructs in calls to the JS runtime for Oak (like __oak_eq and __as_oak_string), and because certain constructs like assignments need to be expanded out into longer sequences of expressions in JavaScript to preserve Oak semantics. However, a naive approach to codegen frequently resulted in redundant, computationally expensive expressions being generated when a much simpler one would have done.

As an example, let’s take this trivial expression to index into a list of children of some node object.

node.children.(childIndex + 1)

Before these optimizations, a naive codegen for this would produce the JavaScript expression below. (Note that all generated code is minified. I’ve expanded it out here for, uh, readability.)

(() => {

let __oak_acc_trgt = __as_oak_string(

(() => {

let __oak_acc_trgt = __as_oak_string(node);

return __is_oak_string(__oak_acc_trgt)

? __as_oak_string(__oak_acc_trgt.valueOf()[children]) || null

: __oak_acc_trgt.children !== undefined

? __oak_acc_trgt.children

: null;

})()

);

return __is_oak_string(__oak_acc_trgt)

? __as_oak_string(

__oak_acc_trgt.valueOf()[

(() => {

let __oak_node = __as_oak_string(childIndex + 1);

return typeof __oak_node === "symbol" ? Symbol.keyFor(__oak_node) : __oak_node;

})()

]

) || null

: __oak_acc_trgt[

(() => {

let __oak_node = __as_oak_string(childIndex + 1);

return typeof __oak_node === "symbol" ? Symbol.keyFor(__oak_node) : __oak_node;

})()

] !== undefined

? __oak_acc_trgt[

(() => {

let __oak_node = __as_oak_string(childIndex + 1);

return typeof __oak_node === "symbol" ? Symbol.keyFor(__oak_node) : __oak_node;

})()

]

: null;

})();

Most of these conditionals and function expressions are here to deal with different runtime types that can usually be statically verified never to occur. For example, it is illegal to index into a string value with a property name, like myString.children. Using these compile-time cues, we can eliminate these branches and shorten other ones. After this round of optimizations, the same Oak expression generates much simpler code.

__oak_acc(

((__oak_acc_tgt) =>

__oak_acc_tgt.children !== undefined

? __oak_acc_tgt.children

: null)(node),

__oak_obj_key(__as_oak_string(childIndex + 1))

)

Without reducing the size of individual variable names, this is the simplest way to express the semantics of the original Oak expression – we cannot predict the runtime value of the .children property (without static type checking, which I might pursue in the future), so we must be ready to handle undefined values. We need to reference the value of node twice in the ternary expression, and we can’t do that without wrapping the whole conditional in a new function scope. The __oak_acc and __oak_obj_key runtime calls are needed to ensure that property accesses with certain types of keys follow Oak’s language rules.

One other codegen pattern that was useful enough to note here is moving variable declarations from let statements to function arguments. In other words, declaring new lexical scopes for variables like this

() => {

let first, second;

first + second;

}

is equivalent to writing the much more concise expression

(first, second) => first + second

This pattern leads to shorter generated code in many cases, because of additional optimizations it enables like eliminating the wrapping { ... } block.

Speeding things up

The next significant change impacted how Oak’s if expressions were compiled down to JavaScript. Oak has exactly one universal way to express conditionals, which looks like this.

if n % 2 {

0 -> :even

_ -> :odd

}

Depending on the context, if expressions can take on a few other shorthand forms.

if MobileWeb? -> {

client.addTouchHandlers()

}

if {

MinWidth < width

width < MaxWidth

config.overrideAspectRatio? -> lockAspectRatio()

_ -> unlockAspectRatio()

}

Oak’s compiler had inherited a pattern from Ink’s September compiler when I first wrote it, and it used to generate

__oak_if(n % 2, [

[() => 0, () => Symbol.for("even")],

[() => __Oak_Empty, () => Symbol.for("odd")],

]);

The most recent version of oak build compiles the same Oak expression down to

((__oak_cond) => __oak_eq(__oak_cond, 0)

? Symbol.for("even")

: Symbol.for("odd"))(n % 2)

This version invokes JavaScript’s ternary (conditional) expressions directly. It pays no overhead cost for closures, arrays, and the __oak_if function call we needed to express the same logic prior to the change. Using JavaScript’s native conditionals also enables JS engines to JIT compile the conditional to efficient machine code that can take better advantage of the CPU branch predictor. As we’ll see, all of this results in a huge performance bump at runtime.

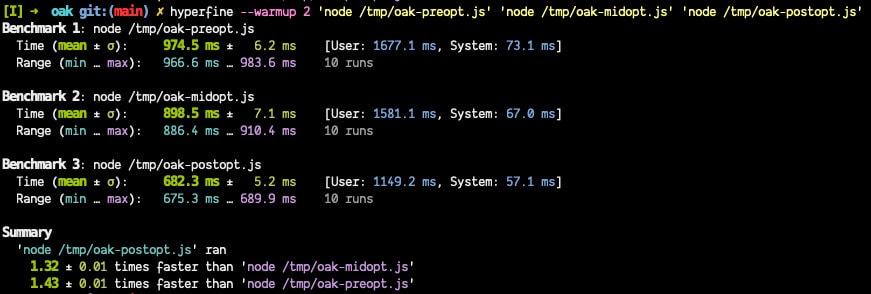

The results

To measure the impact of these optimizations on something that resembles real-world code, I ran these comparisons on the compiled output of Oak’s behavioral test suite, which consists of around 850 unit tests written in Oak. The total sum of these tests is pretty close to “real-world” code, but I validated these results against a (currently private) repository of around 3k LOC of Oak code, which showed similar improvements.

I also used this opportunity to try out Hyperfine, a pretty sleek command-line benchmarking tool. I can pass it a couple of shell commands to run, and Hyperfine will take care of warming up (or clearing) the filesystem cache, measuring statistical variance across multiple runs, pointing out any outliers, and neatly summarizing the result into a quickly digestible “X ± Y seconds” format. This is the first time I’ve used Hyperfine, despite having seen it in the wild many times, and I was immediately sold.

But before we get to Hyperfine’s measurements of runtime performance, here is a look at the raw code size of generated binaries.

$ ls -l *.js

-rw-r--r-- thesephist 639563 Jan 26 18:32 /tmp/oak-preopt.js

-rw-r--r-- thesephist 427482 Jan 26 18:32 /tmp/oak-midopt.js

-rw-r--r-- thesephist 431806 Jan 26 18:32 /tmp/oak-postopt.js

In these comparisons:

preoptrefers to the “pre-optimization” version of Oak at commit 9ab1dcd, before any of the changes discussed in this post,midoptrefers to the version after code size changes but before the if-expression codegen optimization at caeb517, andpostoptrefers to the compiled output after all the above optimizations, at the current head ofmainwhich is 1e82d64.

Our code size-focused optimizations reduced the total bundle size by almost exactly one third, which is a pretty significant improvement! The if-expression codegen optimization added back about 1% to the binary size, but I’m pretty satisfied by that figure given the gains we see in runtime speedups.

The code size optimizations by themselves get us about an 8% improvement in runtime, but together with the if-expression optimization, the final binary runs 43% faster! This also means running Oak programs by first compiling them to JavaScript to run on a modern JS engine like V8 is now about twice as fast as running Oak programs natively using the oak CLI, which I’m pretty happy with.

Despite these improvements, there are many compiler optimizations that haven’t been possible yet in oak build due to the current architecture. oak build’s current semantic analysis is quite weak, only transforming recursive functions and annotating variable declarations. With further passes on the AST before codegen, we should be able to perform more advanced optimizations like dead code elimination and common subexpression elimination, which should show further marked improvements to both code size and runtime performance of ahead-of-time compiled Oak programs.

A more ambitious future goal for Oak is to have a strictly-typed subset, something along the lines of the Teal type checker for Lua. Static type annotations should let us take the optimizations discussed above much further, by predicting runtime types and eliminating branches that won’t be taken.

But all of this is a dream, and I think this week’s changes are a good start. As I build more complex applications in Oak, it’s good to feel the performance ceiling lift ever so slightly higher. Onwards!

← Behind the scenes: building the Ink codebase browser