Although Ink is over a year old now, it has never had a dedicated syntax highlighter. When I write Ink programs, which is the vast majority of my time reading Ink code, I’ve used a vim syntax file to take advantage of vim’s syntax highlighting capabilities. But often I just need to cat an Ink program source file, and for obvious reasons, there hasn’t been an off-the-shelf syntax highlighter I could depend on for simply viewing Ink programs.

Recently, I wrote September, which was designed to become a self-hosting Ink-to-JavaScript compiler. But as a part of the project, I wrote a tokenizer and a parser for Ink that were written in Ink itself and easy to hack on. I thought this would be a good base on which to build a simple syntax-highlighting cat replacement for Ink code.

This became the september print command.

In addition to translating Ink programs to JavaScript, September can now print syntax highlighted Ink code. This was a quick addition to the toolchain – about 2 hours of work. Here’s what changed. (If you find this post hard to grok, you might want to reference my post about how September works first, then come back.)

Computing spans during tokenization

All good tokenizers produce tokens that contain some positional information for each token, like a line number and column number, to help debug programs produced by the compiler. Some tools keep richer location information than others. Until now, September’s tokenizer simply recorded a line and col property for each token, recording the line and column number at which the token started. On a compiler error, September would output the line and column of the token where compilation failed.

To syntax highlight a text file, we need to ultimately compute spans. A span is just a piece of data containing where in the text file a token begins, and where it ends. In a trivially simple program like this

num + 2

we could compute the following spans.

span | token

[0, 4] | num

[4, 6] | +

[6, 7] | 2

While it’s strictly possible to compute spans from line and column numbers of tokens by referencing the original source file, it would have been needlessly complicated to get it right. So instead, I updated September’s tokenizer to add a new property to each token data structure: its starting index in the original source file. With this data about each token, I could construct a span for a given token by taking the token’s starting index as the span’s start, and taking the next token’s starting index as the span’s end.

The highlighter uses this exact algorithm to compute a span for every token in the token stream, from which we can syntax-highlight an entire file.

Tokenizing comments

Until now, Ink’s language tooling never needed to know about comments, so they were simply ignored during tokenization and parsing in all of the compilers and interpreters. But I wanted to correctly syntax-highlight comments in a de-emphasized gray color, which meant Ink now had to tokenize comments properly.

Handling comment tokenization correctly throughout the entire compiler would have been nontrivial, because of the way tokens interact with Ink’s Separator token (,). These expression-terminating tokens are implicit and auto-inserted by the tokenizer during scanning, akin to JavaScript’s automatic semicolon insertion. Comments can appear in all sorts of weird places – next to infix operators, right before parentheses in a function call, before a closing parenthesis, in between a unary not ~ and its operand – and I thought trying to make the automatic comma insertion rule smarter would have been more complex than simply making comment tokenization optional.

So Ink’s tokenizer in September now has an extra option, lexComments, that can be flipped on to add comment tokens into the token stream. The tokenizer doesn’t provide any guarantees about whether the token stream can be parsed correctly with comments, but we don’t need that guarantee for syntax highlighting.

I imagine there might be a future use case where we’d want the comment-enabled token stream to be fully correct, but I’m betting that we can handle that transition when we need to.

For now, Ink has a new type of token, Tok.Comment, that includes the full text of a comment node.

Syntax highlighting based on tokens

With accurate span information and well-tokenized comments, we’re finally ready to syntax highlight an Ink program. Most of the hard work is already done. Here, we simply need to color each substring of the program source file by what type of token it contains. For example, in the above code snippet num + 2, we could say:

numis aTok.Ident(identifier), so don’t color it+is an infix operator, so color it red2is a number literal, so color it magenta

These are arbitrary coloring rules, but this illustrates the process. Because we have a list of all possible token types, we can simply associate each token with a color that we think make sense. Then we can iterate through the entire token stream, and for every token, we produce a correctly colored substring of the original program by referencing the token’s span. In the end, we’re left with a list of correctly syntax-highlighted substrings of the original program, which we can simply concatenate together to produce a fully highlighted source file.

To apply color to text, we use ansi.ink, a color terminal printing library for Ink. The ansi library gives us functions to produce colored versions of a string. For example, we cay say (ansi.Red)('hello, world') to produce a version of the string ‘hello world’ that would display in red when printed to an ANSI compliant terminal.

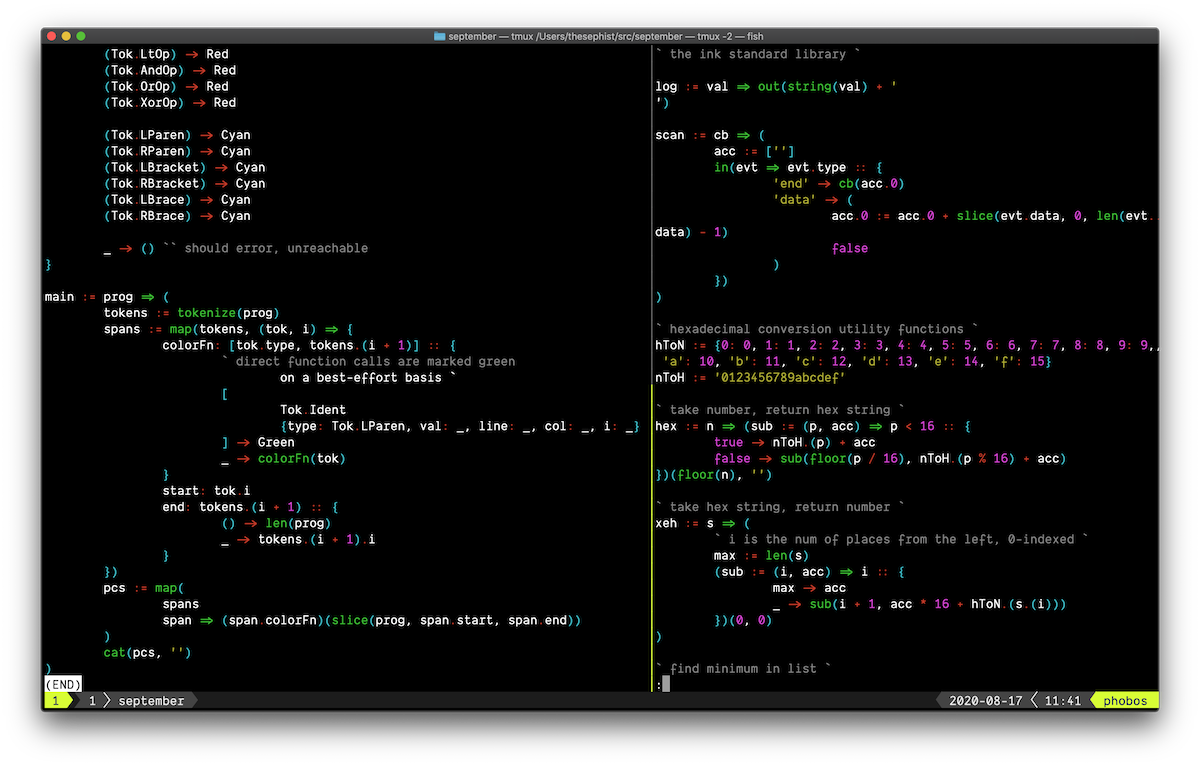

All this happens in the highlighter’s main function:

`` src/highlight.ink

main := prog => (

`` tokenize the program

tokens := tokenize(prog)

`` compute a span for each token

`` we also determine a colorFn for each token,

`` depending on its type.

spans := map(tokens, (tok, i) => {

colorFn: [tok.type, tokens.(i + 1)] :: {

` direct function calls are marked green

on a best-effort basis `

[

Tok.Ident

{type: Tok.LParen, val: _, line: _, col: _, i: _}

] -> Green

_ -> colorFn(tok)

}

start: tok.i

end: tokens.(i + 1) :: {

() -> len(prog)

_ -> tokens.(i + 1).i

}

})

`` create highlighted "pieces" of the program by applying

`` each token's colorFn to its span text

pcs := map(

spans

span => (span.colorFn)(slice(prog, span.start, span.end))

)

`` concatenate highlighted pieces together for a final output

cat(pcs, '')

)

There are some limitations to this approach:

- Because we are highlighting from a token stream, we have very little semantic information available to us through the process. This means we can’t do things like highlighting identifiers based on type, or based on whether one is an argument or a local variable.

- We will attempt to correctly highlight incorrect programs that would otherwise contain syntax errors.

- Because the highlighting logic defined here is tied closely to September’s tokenizer, we can’t reuse any logic here to write syntax highlighting rules for other environments like GitHub’s

linguistor Visual Studio Code.

For my purposes of building a better cat for Ink programs though, none of these are deal breakers.

From now, whenever I want to read an Ink program file in the terminal, rather than opening up a new Vim buffer, I can simply september print file.ink. How nice!