Last month, I launched Eliza, a chatbot modeled after the classic MIT conversational program and written entirely in Ink. Though the project itself isn’t novel or interesting – it’s mostly a port of existing implementations of ELIZA – Eliza is built as an isomorphic Ink application, meaning a substantial part of the codebase can run both natively, on a server, and on the client (a Web browser).

See Eliza on GitHub Try Eliza →

This allows Eliza to have both a command-line interface and a Web app. The CLI runs on a native Ink interpreter like the Go-based interpreter and the Web UI is Ink compiled down to JavaScript with September.

For an app like Eliza, where the critical business logic (the code for generating a response to a user query in this case) is independent of a particular runtime platform, writing Ink programs that can run anywhere is useful. It means we can write one implementation of some logic and literally reuse it in many different clients. In fact, the Ink standard libraries (std and str) have already been used in this way in the September compiler when compiling Ink programs to JavaScript. Eliza takes this to the next level and runs much more complex logic, like the conversational algorithm, across platforms.

In this post, I want to give a brief overview of the Eliza project and share the process of building a real-world isomorphic app in Ink.

Eliza, a chatbot written in Ink

The original ELIZA was one of the first “chat bots”. Invented in the MIT AI lab in the mid-60’s, it demonstrated how a simple algorithm based on matching patterns in language against a database could emulate reasonable human conversations, and became one of the first candidates for real “Turing tests”.

Eliza works by taking a line of input from the user and breaking it down into meaningful recognized pieces by running through a list of predefined rules called a “script”. Here’s a sample of the “doctor” script, which is one of the most popular scripts for Eliza. It’s the script that the Ink version also happens to use.

key: if 3

decomp: * if *

reasmb: Do you think its likely that (2) ?

reasmb: Do you wish that (2) ?

reasmb: What do you know about (2) ?

reasmb: Really, if (2) ?

key: dreamed 4

decomp: * i dreamed *

reasmb: Really, (2) ?

reasmb: Have you ever fantasized (2) while you were awake ?

reasmb: Have you ever dreamed (2) before ?

reasmb: goto dream

In general, a script file works a little bit like regular expressions. Each rule matches against a specific pattern, like if 3, and generates a list of possible responses by randomly selecting from the “reassembly” options outlined in the script, filled in with pieces of the user’s original question or prompt.

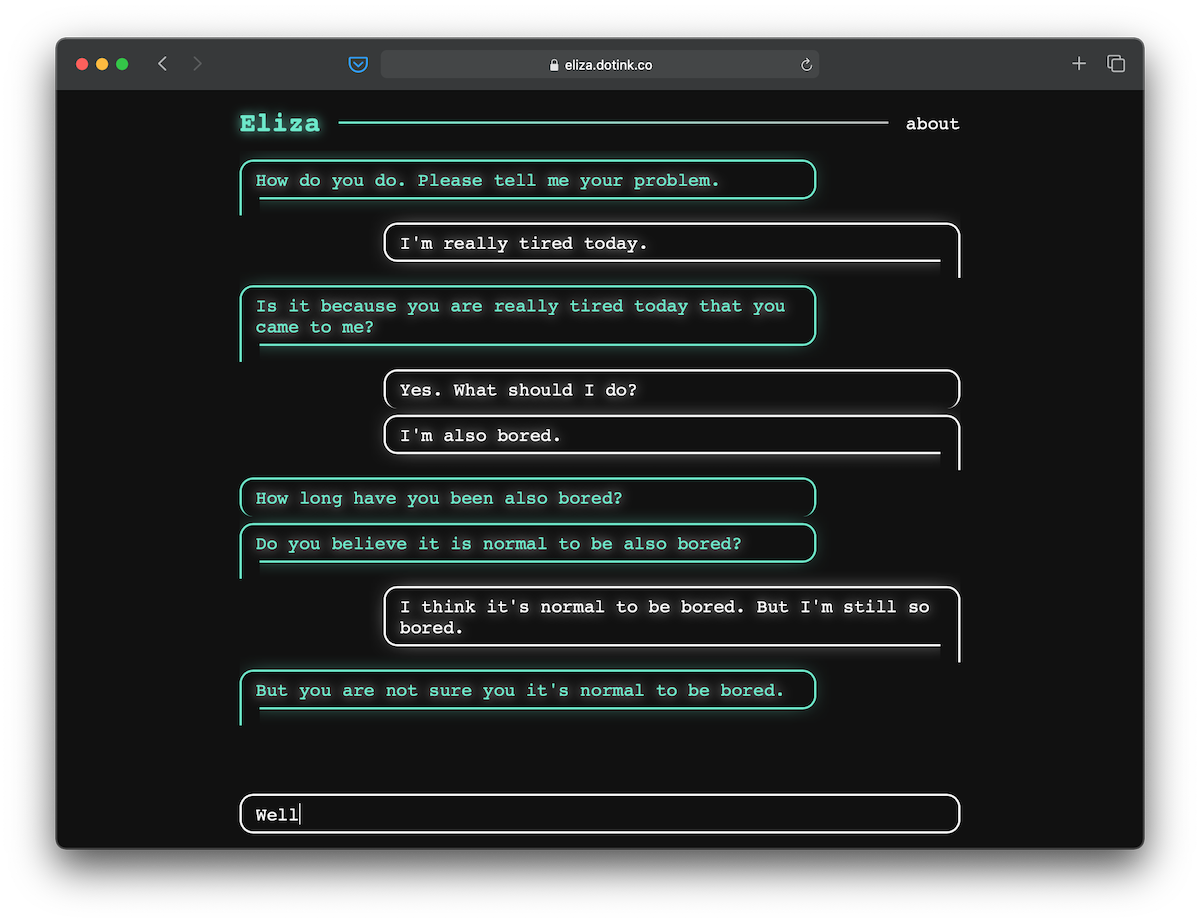

I ended up wrapping the conversational bot within a chat app-like interface, which you can try here.

Eliza’s algorithm is an interesting demonstration of the simplicity of most of our human conversations, because it often generates plausible responses (especially with more extensive predefined scripts), but there are also very clear limitations. For example, it can’t generate completely original responses that aren’t in a script, the way that modern language models easily can.

The Ink implementation of the Eliza algorithm is a modified port of a Python implementation at gezhiggins/eliza.py. Because semantics of Python and Ink are quite similar (they’re both dynamically typed interpreted programming languages with objects and maps at core), it was straightforward to port a Python implementation into Ink. The algorithm works by first parsing the script file into a structure optimized for lookup, and then taking in one line of input at a time to generate potential responses. After a short conversation, if the user goes off topic into something the algorithm doesn’t understand, there’s even a memory-like mechanism to bring up previous topics to get back on track.

Of course, the most interesting part about Eliza is not the algorithm itself, but the fact that it runs on both the server and the browser.

Making isomorphic Ink possible

The premise of isomorphic Ink is that Ink, the core language, is a platform-agnostic high-level language, and it can execute on a huge range of potential environments. Among them are native, enabled by the main Go interpreter and the Rust interpreter, and JavaScript, with the September compiler. To run the same nontrivial algorithm on multiple runtimes, we need to first ensure that the language implementation is identical across all the runtimes. Ink does this with an extensive test suite that tests implementations of not only the core language, but also a significant portion of the standard library. This enabled me to use the same Ink program on multiple platforms fearlessly, without worrying that implementation differences in edge cases were going to get in the way and lead to bugs.

The September compiler transforming Ink to JavaScript is the core of isomorphic Ink code, but to build a useful nontrivial web app like Eliza, we need more than just Ink programs running in the browser. We need, for example, an easy idiomatic way for Ink programs to access the DOM. To help bridge this interface gap, I brought in an older project of mine – Torus.

Torus ❤️ Ink

Torus is a small minimal JavaScript library for building user interfaces on the Web. The library includes a few tools for managing local state in JavaScript applications called Records and Stores, and a component-based UI rendering system for building web UIs productively with JavaScript. While those APIs provide elegant interfaces for their job for JavaScript programs, they’re class-based and unideal for Ink apps to use. Instead, Ink borrows a deeper, more fundamental part of Torus that enables Torus to be fast and elegant, the virtual DOM-based UI rendering function Torus.render.

Torus, like React, allows a program to define a user interface declaratively as a function from data to a tree of components. Both libraries have renderers that take the produced tree of components and compare it with the previously rendered tree to produce a list of DOM manipulations that they make to update the view. Torus’s renderer is much simpler in design that React, and it’s called Torus.render. Every UI component in Torus internally depends on Torus.render to take the virtual DOM produced and render any changes to the page.

To build Eliza, I borrowed this renderer layer from Torus by importing the Torus library onto the page, and wrote a small adapter library called torus.js.ink that provides an idiomatic Ink API for the Torus renderer.

With the adapter, getting a basic web UI running as simple as the Ink program

` find an element into which we render the app `

root := bind(document, 'querySelector')('#root')

` define the app as a function of state => DOM tree `

App := state => (

update := Renderer(root).update

` we can call "update(vdom)" to re-render the app `

update(

h('div', ['app'], [

str('Hello, World!')

])

)

)

The Renderer Ink function wraps Torus’s render function so that calling Renderer.update will re-render an app with a new virtual DOM. Eliza’s UI is written exactly this way – every time the application state changes, a global state variable is updated and the entire app is re-rendered with the minimum set of DOM mutations dispatched through the Torus renderer. The beautiful benefit of Ink and Torus working together like this is that Torus promotes a functional style of writing user interfaces – data flowing through functions – and Ink is primarily a functional programming language. So when they come together, they fit together very well. Dare I say, using Torus from Ink was as fun as using Torus from JavaScript.

Personally, this is by far the coolest part of Eliza. Torus and Ink are two of my biggest side projects, and to see them fit and work together like this through an Ink-based compiler is a holy grail moment.

Future work

I enjoyed building Eliza across native and Web, but the overall experience of building a Web app in Ink still has lots of shortcomings. Two of the most important missing pieces are both shortfalls of the September compiler itself: module loading and source maps.

So far, September has mostly been used for single-file programs, and September provided a pre-compiled JavaScript distribution of the Ink standard library. As a result, projects could get by without support for a way for Ink to load() other Ink programs when compiled to JavaScript. However, Eliza was a complex enough project that I would have appreciated proper module support in the September compiler. Without it, I had to manually clean up parts of the compiled JavaScript bundle to ensure different program files interacted correctly.

Source maps are a standardized way for compiled JavaScript bundles to be debuggable. A JavaScript bundle can provide “source map” metadata so that a debugger can map offsets in the compiled bundle to offsets in the source file (an Ink source file in this case). Even for languages that don’t resemble JavaScript at all, like ClojureScript, sourcemaps provide a usable debugging experience over the printf-style debugging I had to resort to without it while building Eliza. September currently has source map support on the roadmap – I’m hopeful I can get to it soon.

Eliza was a cool project for me in many ways. I think it looks slick, and it works well as a chat interface. But my favorite part about Eliza is obviously that it marries two of my longest-running projects, Torus and Ink, into a good developer experience for me. And now that the floodgates to Ink on the web has officially opened, I’m excited to build many more projects on the Web with Ink going forward.

← Assembler in Ink, Part II: x86 assembly, instruction encoding, and debugging symbols

Ink playground: the magic of self-hosting a compiler on JavaScript →