Contents

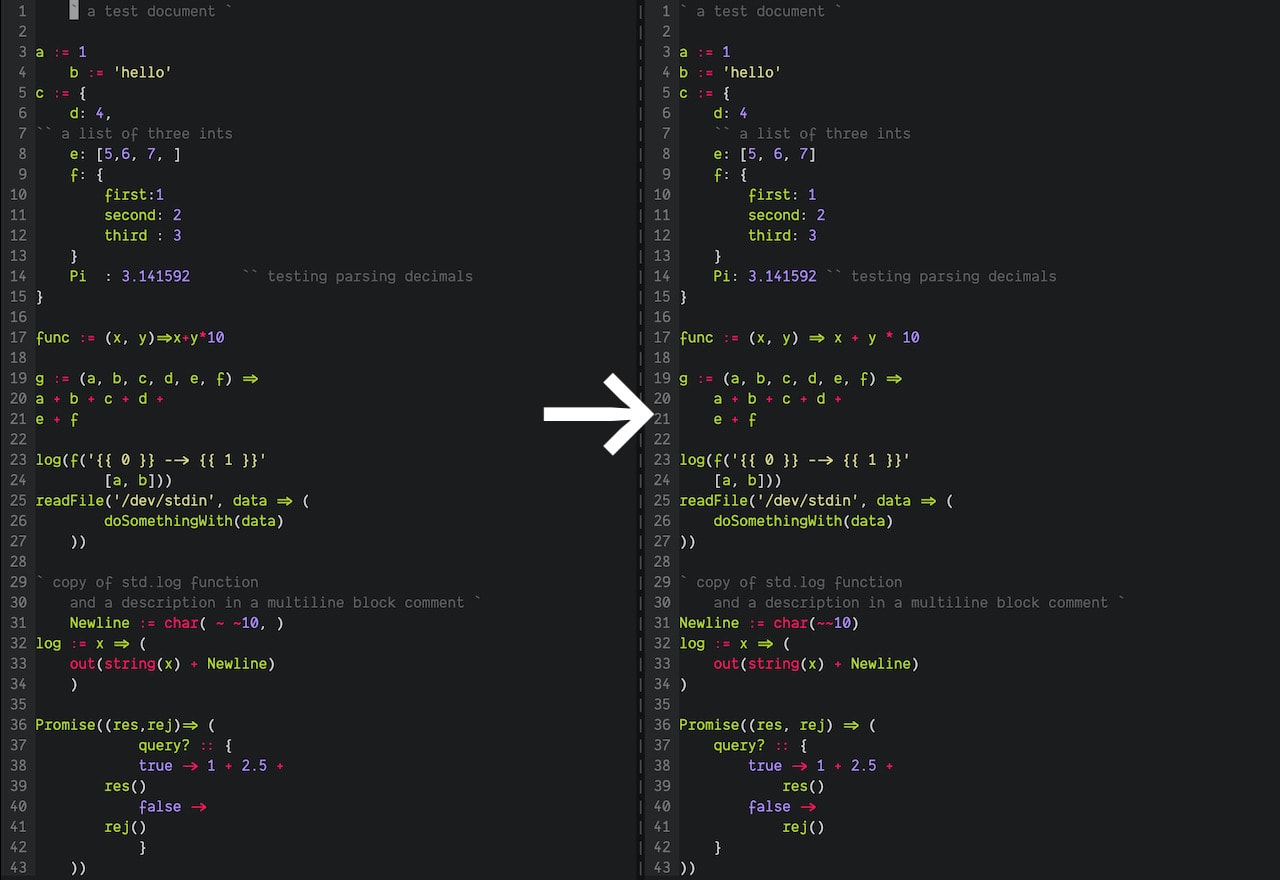

inkfmt (pronounced “ink format” or sometimes “ink fuh-mt”) is a self-hosting code formatter for the Ink language. This means inkfmt takes valid Ink programs and normalizes the formatting of the code to be readable and clean. inkfmt is itself an Ink program, and inkfmt uses itself to format its own source code. (This is the “self-hosting” bit.)

inkfmt isn’t perfect yet – it’s a work in progress – but it currently produces the correct output about 95% of the time with idiomatic Ink code. Code formatters in general are fascinating, and inkfmt specifically was one of the most interesting technical projects I’ve worked on recently (I had to switch from pen-and-paper to my whiteboard for the first time in a while!), so I wanted to share what I’ve encountered so far.

What’s a code formatter?

In the course of programming, we add and remove pieces of text from our program source code many thousands of times. This process of exploration usually also leads to the shape of our program changing over time, as you try to lay out your code in a way that’s readable to you, and makes sense to others.

If a team of developers all do this over the same body of source code, you’ll often come across changes in code that don’t really change what the program does or how it behaves, but changes the layout of the code. Sometimes they’re meaningful, but most of the time, these changes like changing the amount of whitespace, re-indenting code, and converting tabs to spaces are more distracting than useful.

A code formatter, sometimes called a “pretty printer”, takes a bit of source code and makes small transformations to it to produce a more readable, visually clean version of the same program, and in the process, removes any frivolous changes in whitespace, indentation, and more. It helps team members settle on a single style of code formatting, makes code more readable, and usually saves time, too.

For this reason, most popular languages that emerged in the last decade ship with code formatters. Go popularized this trend with gofmt, Rust has Rustfmt, Zig has zig fmt, Dart has dartfmt, and JavaScript is rich with many alternatives like Prettier and Standard. They not only clean up the code, but provide a single, canonical formatting for a program so we programmers don’t spend time mentally litigating the various ways a particular expression or function could be written out.

Developers use code formatters in two major ways, either integrated into their text editor/IDE, to format on save or a keyboard shortcut; or integrated into their change control workflow, so code changes are formatted before they’re shared with the team and the world. But in order for a language to support any of these use cases, it needs a code formatter, a program that takes some bit of source code and produces a correctly formatted version of it.

That is what inkfmt does today.

What inkfmt does

inkfmt is currently just an MVP, and does exactly one thing. It takes a single input file, formats the code inside, and returns the output. And it does that job reasonably well, though there still definitely are rough edges. It takes input from /dev/stdin and outputs to /dev/stdout. This means we can run inkfmt on a file like this in the shell.

inkfmt < input.ink > output.ink

Eventually, I want to build out a command-line tool that allows me to do this for a large tree of files and format code in-place.

inkfmt currently makes four types of code transformations.

- Remove trailing commas at line endings. In C-like programs, statements are terminated with the semicolon. Ink’s analogous line terminator is the comma. But this isn’t enforced at the source-code level, only in the language grammar. The Ink interpreter uses automatic comma insertion (like JavaScript’s ASI) to insert missing commas where appropriate. This means in idiomatic Ink code, lines don’t end with commas. inkfmt removes such trailing commas at line endings.

- Remove trailing commas in lists. Ink also allows commas to follow a list of items:

In such lists, well-formatted code should omit the last comma for visual consistency, and inkfmt makes this transformation automatically, removing the last comma.list := [1, 2, 3, 4, ] object := { key: 'value', apple: 'fruit', } - Re-indent code. Indentation is one of the main ways we visually make sense of code before diving into it. inkfmt uses a deterministic algorithm to calculate a single correct indentation for a source file and applies it to the code. The current algorithm isn’t perfect, but gets us 90% there.

- Canonicalize whitespace between symbols. Within each line, whitespace (and the lack thereof) between expressions help readability. Ink also deterministically adds and removes whitespace between symbols on the same line to settle on a single correct format, opting for spaces between binary operations like

+and&, and no spaces within parentheses and brackets.

Prior art

Like parsers and compilers, pretty printers come from a long and rich historical and academic context. My favorite read on the topic so far is A prettier printer by Phil Wadler from the University of Edinburgh. It’s an academic investigation into the theoretical problem of pretty-printing text. The paper is heavy on functional programming concepts, so it might be unwieldy to some as it was for me at first.

From the other side of the industry, a more accessible and interesting deep-dive into the code formatting problem is The Hardest Program I’ve Ever Written by Bob Nystrom, about the Dart language formatter, dartfmt. (Coincidentally, he also wrote Crafting Interpreters, one of my favorite resources for hacking on interpreters and compilers.)

Another bank of inspiration is the wealth of currently available open-source code formatters for different languages, many of which I’ve outlined above. The code formatting problem rapidly becomes a formidable beast the more we want complete coverage of edge cases, and beyond studying the algorithms and experiments implemented in these formatters, it’s worth knowing what previous edge cases and problems existing code formatters have encountered, and how we achieved consensus on what the formatter should do.

As an example of the kinds of subjective discussions and edge cases code formatting creates, here’s a conversation about rustfmt, and whether the formatter should try to produce consistent line breaks, potentially at conflict with any meaning the programmer may have placed into their own style.

Building inkfmt

I had set up the inkfmt project long ago, because I wanted my text editor (vim) to be able to auto-indent my Ink code on save. Ink’s syntax is unique and we can’t simply use a C-style formatter, so I thought I’d write one myself. And then the project sat and gathered dust without much work.

I’ve started to write more Ink programs recently, so the need arose again, and I thought I’d take a day to bring the project to an MVP level where I could start using it with real projects. I scrapped the boilerplate I had and started over, so inkfmt as of today is about a day’s work, from noon to night.

inkfmt is a little under 250 lines of liberally commented Ink code atop the standard library, and split into two parts: the lexer and the renderer.

The lexer takes a single string of source code and cuts it up into meaningful pieces called tokens. This is sometimes called tokenization or scanning or lexing, but they all mean the same thing. We want to take a single string and cut it up into only meaningful pieces. This tokenization step is also a critical part of most compilers.

the renderer is the inverse of the lexer: it takes a stream of tokens and joins them back together into a single string of source code, albeit one where all the formatting inconsistencies have been ripped out and replaced with what inkfmt thinks is the best solution. inkfmt’s renderer does this by first assembling tokens into lines of text, and then joining those lines together while paying close attention to the indentation between lines.

inkfmt can aptly be described as a program that does the following

print(render(lex(getInput())))

Indeed, the current version of the formatter program does exactly that and little else.

Tokenizers vs. parsers

A tokenizer produces a flat list of symbols, but often, analyzing a program requires something more structured than a list of symbols. Source code usually represents nested, recursive structures – functions and expressions inside other functions and expressions. It’s often useful to have a more complex data structure to represent these nested groups of symbols in programs. We call this next level of representation a syntax tree. A syntax tree describes the nested relationships between different parts of a program. We call the program that generates a syntax tree a parser.

Unlike inkfmt, where the token stream is the core data structure, most code formatters use an abstract syntax tree as the core data structure. I knew this additional complexity was for good reason, especially for languages with richer syntax. The process of building inkfmt’s MVP has been in part a process of discovering exactly why most pretty-printers operate on ASTs and not tokens. Like many other problems in code formatting, better addressing edge cases requires more complexity.

In the beginning, I opted to avoid writing a full parser and AST for inkfmt for a few reasons.

- Potentially wasteful complexity. Ink’s current only parser exists in the Ink interpreter, written in Go. I was set on writing inkfmt in Ink itself, which meant if I wanted an AST-based formatter, I’d at the very least have to port the AST implementation from Go to Ink. I wasn’t sure what other use cases I would have for a self hosting Ink parser, so I wanted to reduce the amount of work I put on myself if possible.

- Ink’s grammar is very simple. Ink’s syntax is modeled after Lisp and JavaScript, but Ink uses very few concepts and special syntax to keep the language small. This means there’s fewer syntax rules and edge cases to think about. I thought Ink’s extreme simplicity would allow a full formatter to be written without having to construct a full syntax tree for a program. It turns out we can get really close, but not perfect, and it requires some clever hacks.

- Prototyping speed. I prefer to get projects to a working state within a day of work if possible, and writing a full AST implementation in addition to the formatting algorithm and tokenizer would probably have pushed this MVP into two-days-or-more territory. I didn’t want to make a longer bet on my motivation lasting than I had to.

Constraints of running without the AST

My choice to forego writing a full parser came with some consequences later on in the process. Ones that I’ve mostly worked around, but issues nonetheless. There are a class of small problems in code formatting that are difficult to solve without constructing a syntax tree for a program. Some of these problems can be hacked around, others can’t.

As an example, take this bit of Ink code.

(A)

1 doSomething(request => (

2 returnResponse(request)

3 )).then(data => (

4 doOtherthing(data)

5 ))

There are two places for us to indent the code, contained within two nested pairs of parentheses. It seems like we could keep track of how deeply nested we are in parentheses at each line of code, and use that to tell us how far to indent each line. But this doesn’t quite get us to the formatting above, which is the desired output.

If we indent each line simply by keeping track of open and closed parentheses, line 3 shouldn’t be indented any differently than line 2. In line 3, we open two parentheses, and close two parentheses. So we’ve opened net-zero parentheses, and we should keep the previous line’s indentation, which is a sensible thing to do in (B) here:

(B)

1 doSomething(request => (

2 returnResponse(request)

3 data := otherThing(f(request))

4 doOtherthing(data)

5 ))

but not in (A) above. In (A), we want the algorithm to realize that this line closes a previous group of expressions, and opens another one. We can’t infer this kind of extra nuance simply by iterating through a stream of tokens. We need to keep track of the order in which expressions are opened and closed, and at that point, we’re effectively building a messy parser.

These issues aren’t very common, but they come up here and there in medium and large codebases, and I think a simple token stream-based formatter will have trouble adapting to these edge cases, even if I can work around some of them today.

The hard thing about indentation

I spent the most time and energy writing inkfmt on the problem of indenting code correctly.

What looks like “good” indentation, it turns out, is a fairly complicated question. This is because there’s a mismatch between the data we’re trying to understand, and the format in which we’d like to have it displayed. Source code is one-dimensional, a single string of text. But displayed on your screen, well-formatted code takes a rich two-dimensional form, and the purpose of indentation is to separate and place these chunks of one-dimensional text in a two-dimensional space, so it’s most readable.

This mismatch means that there isn’t a single simple algorithm to compute how far we should indent every line.

Let’s start with the basics. The first and most obvious rule I implemented was that lines of code inside parentheses and brackets should be indented one level deeper that its surrounding lines. Seems sensible enough. Let’s try to apply it to this snippet.

1 user := {

2 name: 'Linus'

3 place: {

4 city: 'Berkeley'

5 state: 'California'

6 }

7 }

Lines 2 - 6 are easy to think about. We’re inside the curly braces of user := {...}, so we should indent the block one level deeper. But what about line 7? When we reach the start of line 7, we are still inside the curly braces. But we intuitively want line 7 not to be indented, because line 7 closes the group we’ve been indented by.

Okay, I thought, we can simply indent each line after fully processing it, with knowledge of all opening and closing symbols inside it. I then came across this test case.

1 longFunc := (a, b, c

2 d, e) => a + b + c + d + e

Here, we intuitively want line 2 to be indented, because at the end of line 1, our list of arguments is incomplete. But by our rule we just agreed on above, line 2 shouldn’t be indented, because line 2 contains the parenthesis that closes the group it’s indented by.

Okay, what if we only indent a group-closing line if it doesn’t start with some list of values? It’s at this point I started to realize that indentation was a messier problem than I had initially expected.

I can’t go through every single issue I faced building inkfmt’s indentation algorithm, but I want to explore two more particularly interesting cases with you, if you want to dive deeper.

If you’d rather skip to the conclusion, you can click here.

Case study: indentation collapsing

Indentation collapsing is a phrase I made up for a particular condition where the indentation style matches what we want, but some blocks are indented much farther in that we would like. Take this fairly common pattern of passing callbacks into a function.

1 readFile('/my-file', data => (

2 doSomething(data)

3 ))

Let’s continue with our earlier rule of adding an indent level when we enter a parenthesized or bracketed group. That rule tells us that line 2 should be indented twice inwards, because line 2 is contained by two nested groups. First, the readFile(...) group, and then the data => (...) group. But that’s obviously not what we want. We want to indent exactly once for these two nested groups.

So perhaps we can enforce a rule that each line can indent at most one level from the previous line? Not so fast. Consider these more thorny edge cases:

(A)

1 [[

2 a, b, c,

3 d, e, f,

4 ], g, h]

(B1)

1 [[a, b, c,

2 d, e, f]

3 g, h

4 ]

(B2)

1 [[a, b, c,

2 d, e, f]

3 g, h

4 ]

(C)

1 [

2 [a, b, c,

3 d, e, f]

4 g, h

5 ]

- In

(A), we want lines 2 and 3 to be indented in exactly once, even if nested in 2 groups of[[...]]. - In

(B1), however, we want line 2 to be indented in twice, because if we indent it only once as in(B2), it looks liked, e, fandg, hare all in the same level of hierarchy, which is misleading. (C)looks obviously correct to me, and among the choices for our solution to(B),(B1)looks more consistent with it than(B2).

If you, like me, prefer the indentation in (B1), we can’t simply enforce that lines must indent one level at a time. Sometimes, a line should indent two levels at once. So what to do?

My solution to this problem is what I call indentation collapsing. Indent collapsing is one of the last steps of my indenting algorithm. After all other indents have been computed, I scan the prepared output to see if there are any ranges of lines that are indented by more than one level at a time, and then de-indented again by the same amount. In (A) above, for example, line 2 would be indented by 2, and then line 3 would de-indent by 2 again. For these ranges, I trim the indentation to be exactly one level deep.

This additional step in the algorithm turns out to effectively “collapse” deep indents that are visually unnecessary, while allowing the indentation algorithm itself to still think in terms of nested groups of expressions.

Case study: hanging indents

Hanging indents is the most challenging edge case I’ve had to solve today. I’m not completely happy with my current solution, but it works well enough to pass for code that occurs in the wild.

How should we indent this piece of rather gnarly code?

1 addManyNumbers := (a, b, c

2 d, e, f) =>

3 a + b + c + d +

4 e + f

This code is tricky to indent because the particular indentation we probably want isn’t purely a result of any explicit nesting relationships between parts of the syntax.

- We want to indent line 2, because it’s a part of an unclosed list of values.

- We want to indent line 3, the body of the function, because function bodies are generally indented to show nesting.

- We want to indent the last line,

e + f, because it follows an incomplete addition expression from the line above.

Let’s check out our options.

(A)

1 addManyNumbers := (a, b, c

2 d, e, f) =>

3 a + b + c + d +

4 e + f

(B)

1 addManyNumbers := (a, b, c

2 d, e, f) =>

3 a + b + c + d +

4 e + f

(C)

1 addManyNumbers := (a, b, c

2 d, e, f) =>

3 a + b + c + d +

4 e + f

Of them all, I personally think (A) makes the most sense. We keep the second halves of incomplete expressions indented in, but also make sure the function body starts where most function bodies start, at the first indent level. But you’re free to disagree with me on which looks best or is most readable. This is a tricky and sometimes subjective question. I think (B) doesn’t look much worse, though (C) has a little too much going on for my taste.

inkfmt currently produces none of these three, but the original indentation with which I started this example. I think it’s fine, but not ideal. This is another consequence of the limitations of a token stream-based formatter.

This example also illustrates why sometimes code formatting is a matter of taste and personal preferences. This code wouldn’t look great indented in any way, and if I saw this in a real codebase, I’d probably refactor it or restructure it to be more readable and structured, also making it easier to format. But writing a code formatter, we need to consider these stranger edge cases.

Code formatting is complicated because it’s a human problem

Code formatting is different from many other hard computer science problems because the metric that we optimize for isn’t a well-defined measure. Instead, we look for readable, aesthetically satisfying, and useful outputs, and those goals leave a lot of room for subjectivity and taste. I think that’s a big part of the challenge of code formatting.

One of the primary benefits of a code formatter is that it shoulders the responsibility of coding style decisions that are normally given to developers. As a result, writing a formatter is a bit like having those tricky formatting and style discussions all at once, with everyone who might use the formatter, while reaching for a solution with as much generality as we can afford. In subjective problems like this, the cost of this generality is increasing complexity, and I hope you enjoyed witnessing some of that complexity behind the curtain in this post.

Future work

There’s a lot of room to explore beyond the prototype I built today, both in inkfmt itself, and in the larger problem space of code formatting.

On the inkfmt tool, I’d like to come back to it soon to either find clean workarounds for some of the tokenizer-related issues I outlined above, or write an AST-based indenting algorithm that can be correct in more situations. I also want to improve the tool itself, so it can fit naturally into my Ink development workflow, formatting on save in my editors and in pre-commit checks in my repositories. There’s a long way to go.

Ink isn’t a particularly fast language, but I think inkfmt should be able to format tens of thousands of lines of code in under a second. inkfmt can currently format about 1000 lines of Ink code per second, so we have some work to do there in using more efficient data structures and reducing redundant work.

Finally, I want to investigate real-world implementations of code formatters further. Formatters in the wild face a class of challenges that we don’t study as often in academia. Questions like, what should the formatter do when encountering a syntax error? Should it format what it can, or give up? What kinds of hints can the formatter take from comments surrounding a code block to ensure it doesn’t break the author’s original intent? Real-world formatters also have to work incrementally. Large production codebases can range up to tens of millions of lines of code, and formatting any meaningful part of it repeatedly during a work session is going to be slow. Fast formatters only work on pieces of code that have recently changed, and I want to understand incremental parsing and formatting better.

There’s good room for improvements in inkfmt, but working through code formatting as a problem has been one of the most interesting programming exercises I’ve found in a while, with plenty of room to explore further. Importantly, since the formatter is now at a place where I can use it in my day to day development (albeit through an awkward command-line interface), I hope to keep hacking on it as I learn more.