Contents

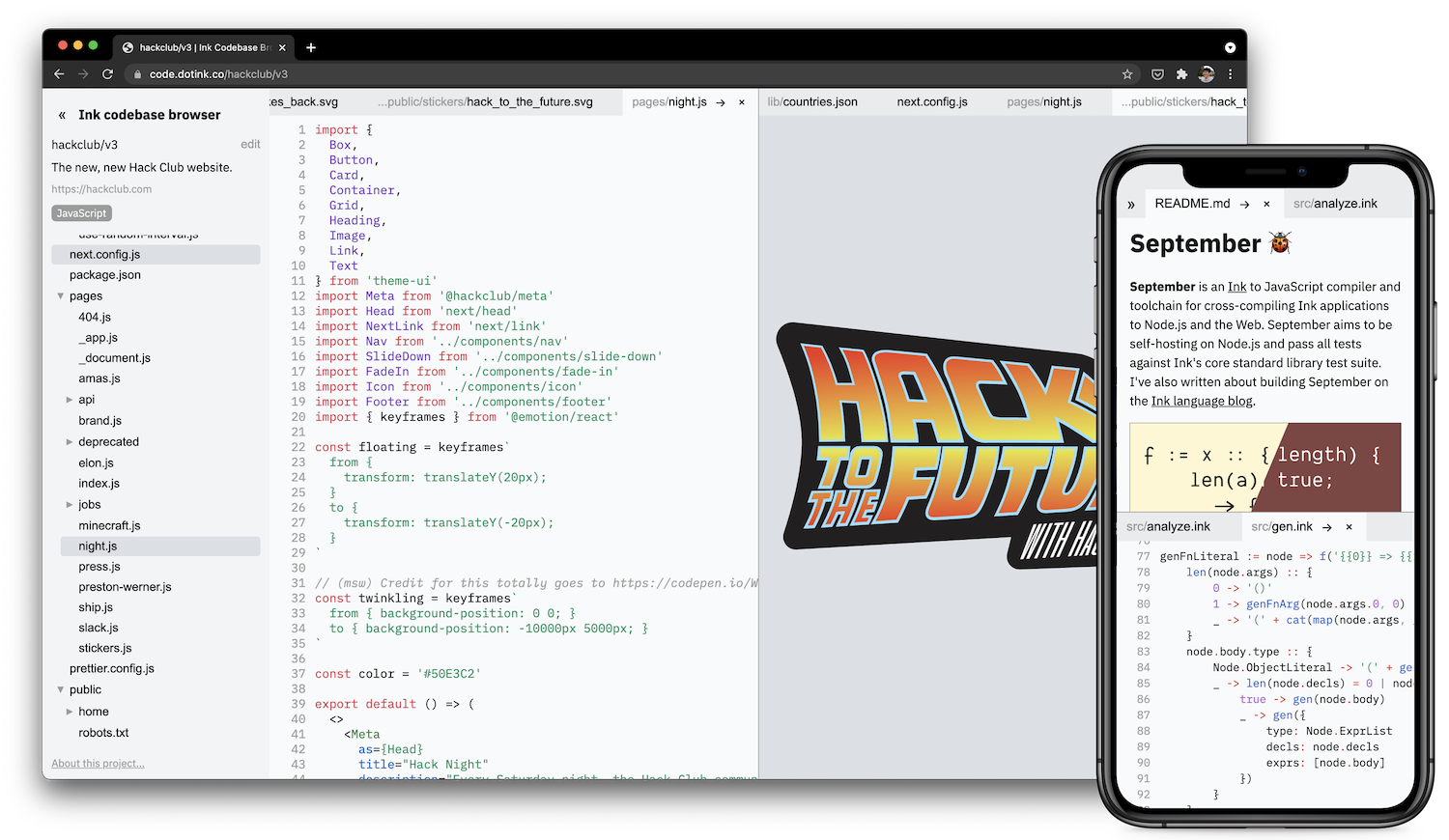

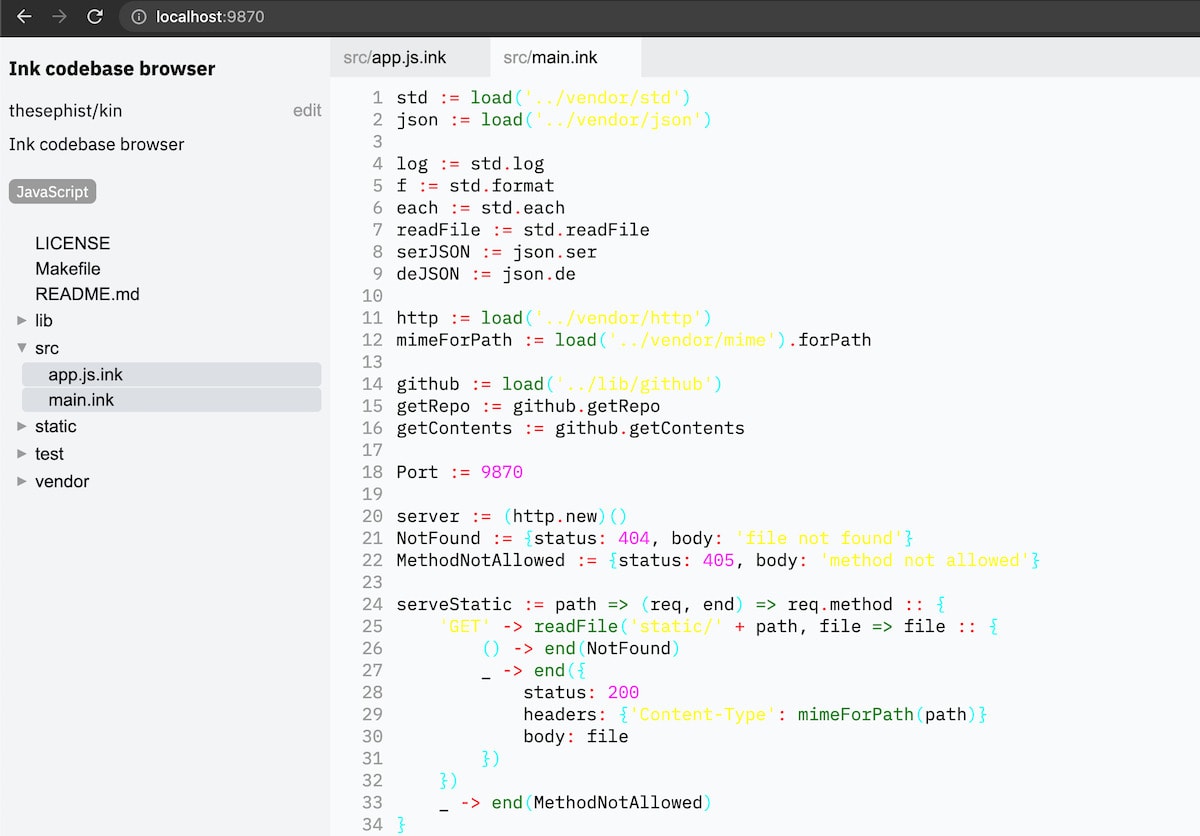

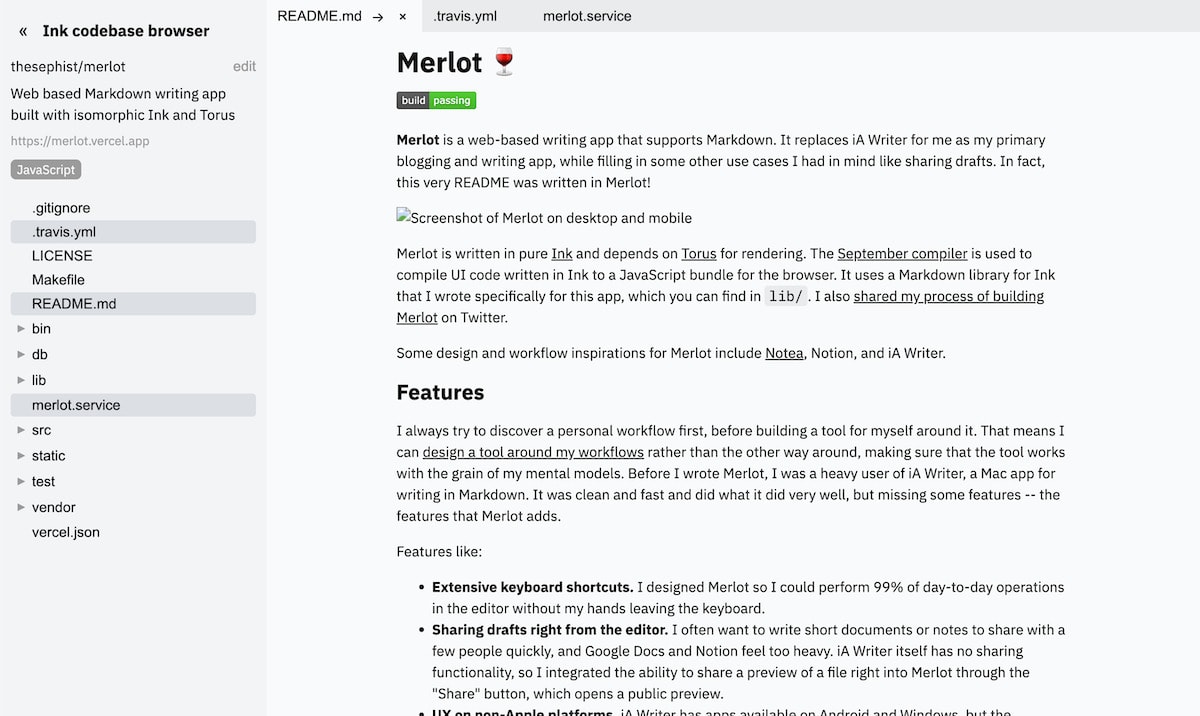

The Ink Codebase Browser is a refined tool for exploring open-source projects on GitHub. Compared to the experience of clicking through file hierarchies and previews on GitHub’s website, this project aims to provide a much better “browsing” experience for online codebases on GitHub with a file tree, rich Markdown and image previews, and multi-pane multi-tab layouts. Because I’ve always found it annoying that I couldn’t yet add Ink syntax highlighting to GitHub, ICB also has first-class support for Ink syntax highlighting.

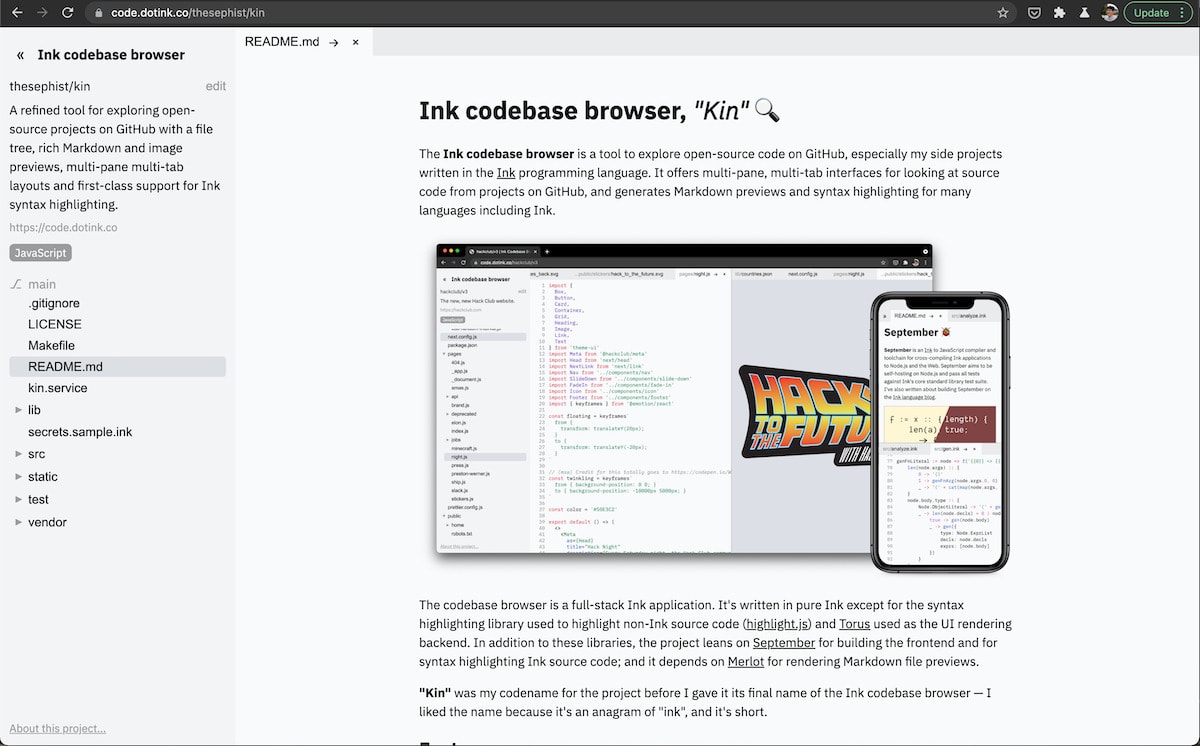

The Ink codebase browser is one of the most complex pieces of software written in Ink to date. It’s a full-stack Ink application, with a server that interfaces with the GitHub API and a client that renders a multi-pane multi-tab UI for a file explorer. It also depends on September for Ink syntax highlighting and Merlot to generate Markdown previews.

This post is a story of going from zero to one, and then to a first “launched” version of the project, in a weekend. Since most of my projects only become public once they’re done, I wanted to take a non-trivial project like this to share how I think about experimenting and prototyping a side project from scratch.

It starts with an experiment

I started work on ICB with a couple of vague problem statements:

- I wanted a wrapper around the GitHub file browser that syntax highlighted Ink code

- I wanted to make a better interface for browsing a codebase than GitHub’s folder-by-folder interface

The first problem was borne out of my frustration whenever I need to go back and read Ink code from my past projects on GitHub. GitHub is frequently the quickest way for me to reference how I achieved something in another project, but without syntax highlighting, it takes me longer to get my bearings in the code. The second problem was inspired by my thinking about the concept of “browsing a codebase”. One way to think of browsing a codebase is to simply iterate through the files and folders, but a much more exciting concept is to also include actions like go-to-definition, running code snippets directly from files, and of course being able to view multiple files together in the same view.

I didn’t have any existing tool for doing the kind of semantic analysis necessary to build go-to-definition for Ink code yet, so I chose to instead build the complex UI component of this idea first. I was inspired by the Unison programming language’s Unison Share interface, and planned to build a code editor-like UI with a file tree on the left and open files on the right.

The very first thing I made after a brief project setup was an interface to GitHub’s API. GitHub conveniently has a JSON API, so I used Ink’s JSON library to validate that I could build functions that correctly interfaced with GitHub. And then I built a server around those functions, to end up with a simple backend server that supported two API endpoints: (1) get some information about a specific repository, and (2) get some information about a specific file path in a given repository. This was enough for me to start building some UI on top.

Next, I tackled the file tree.

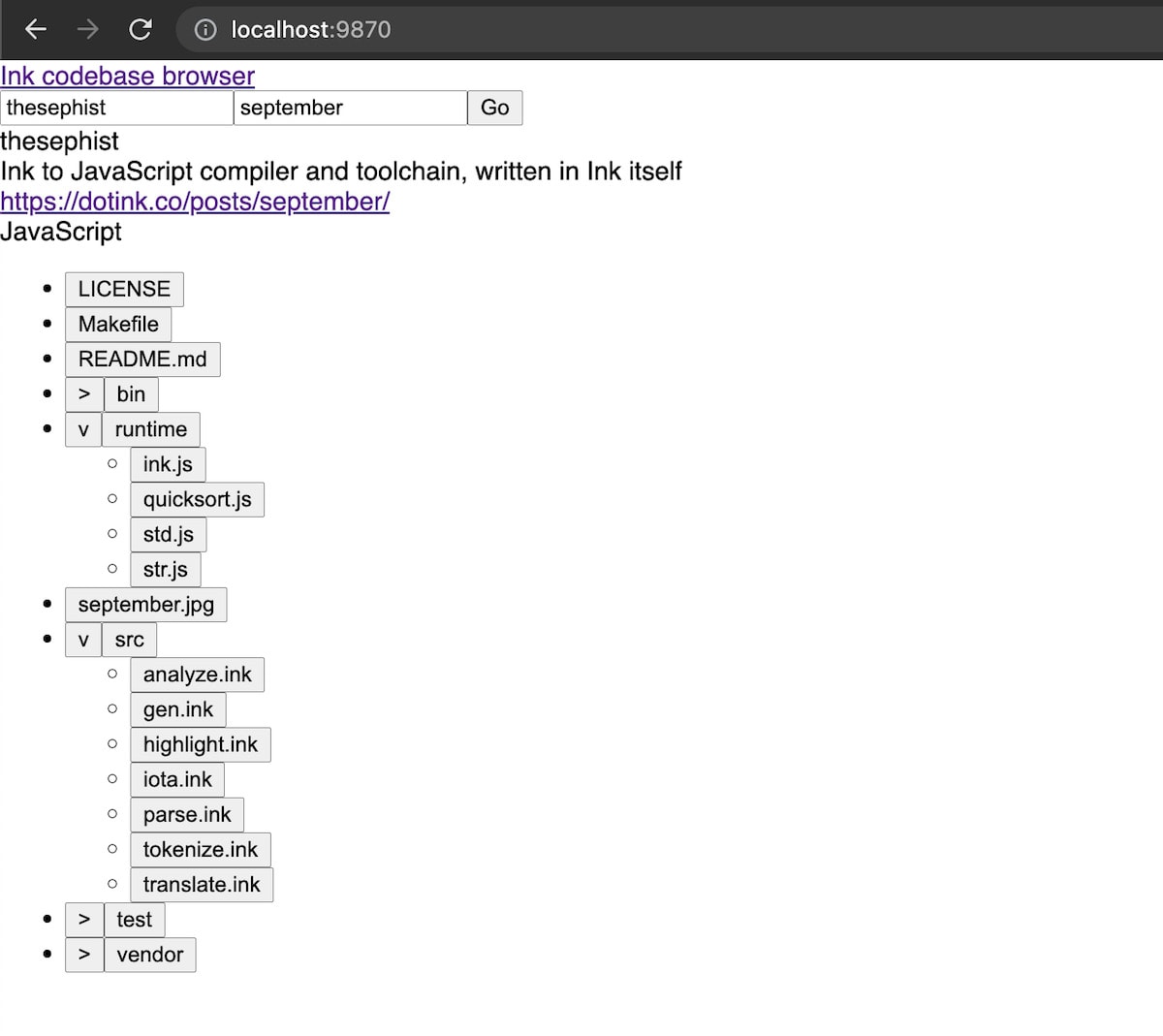

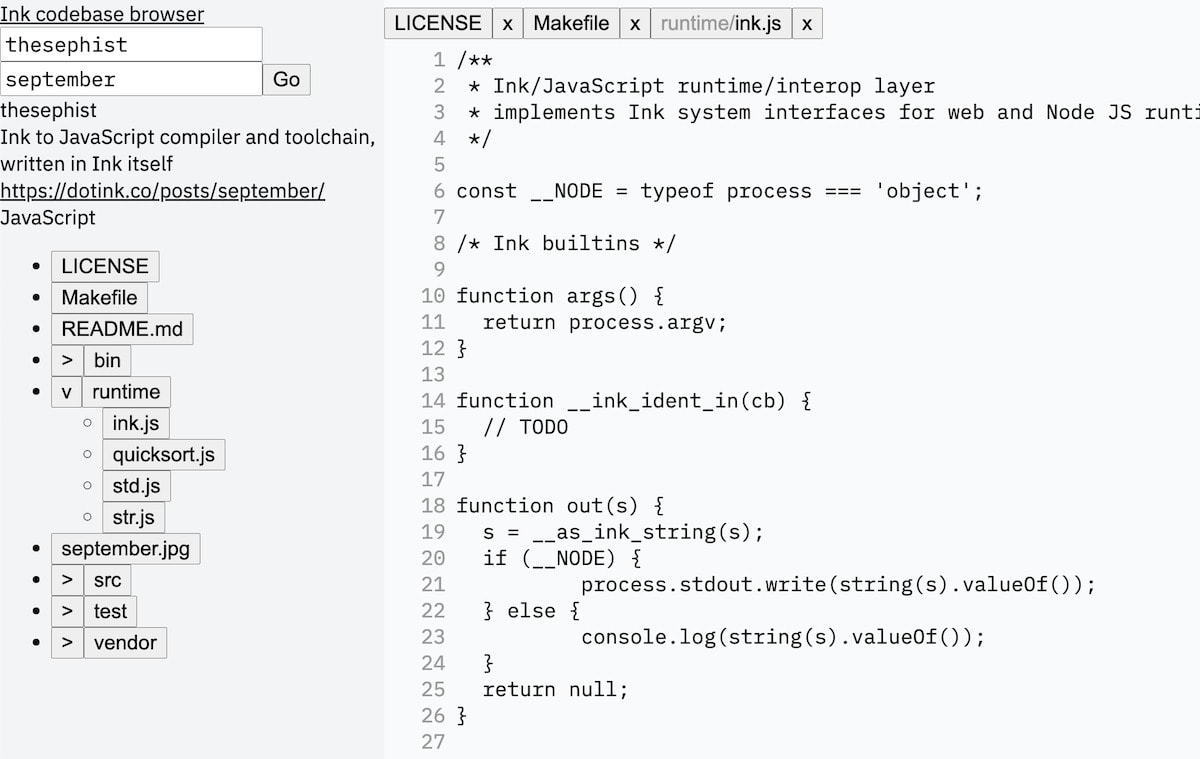

This is the first screenshot I have of ICB in progress. At this point, the app could render two things:

- A “sidebar” (stuck at the top of the page here because of the lack of any CSS) that displayed some metadata about a repository

- A file tree which is just a nested list of

<ul>s. Any “directory” items were expandable with the “v” button, and expanding it would talk to the API to fetch files under that folder and display a new child list of its contents.

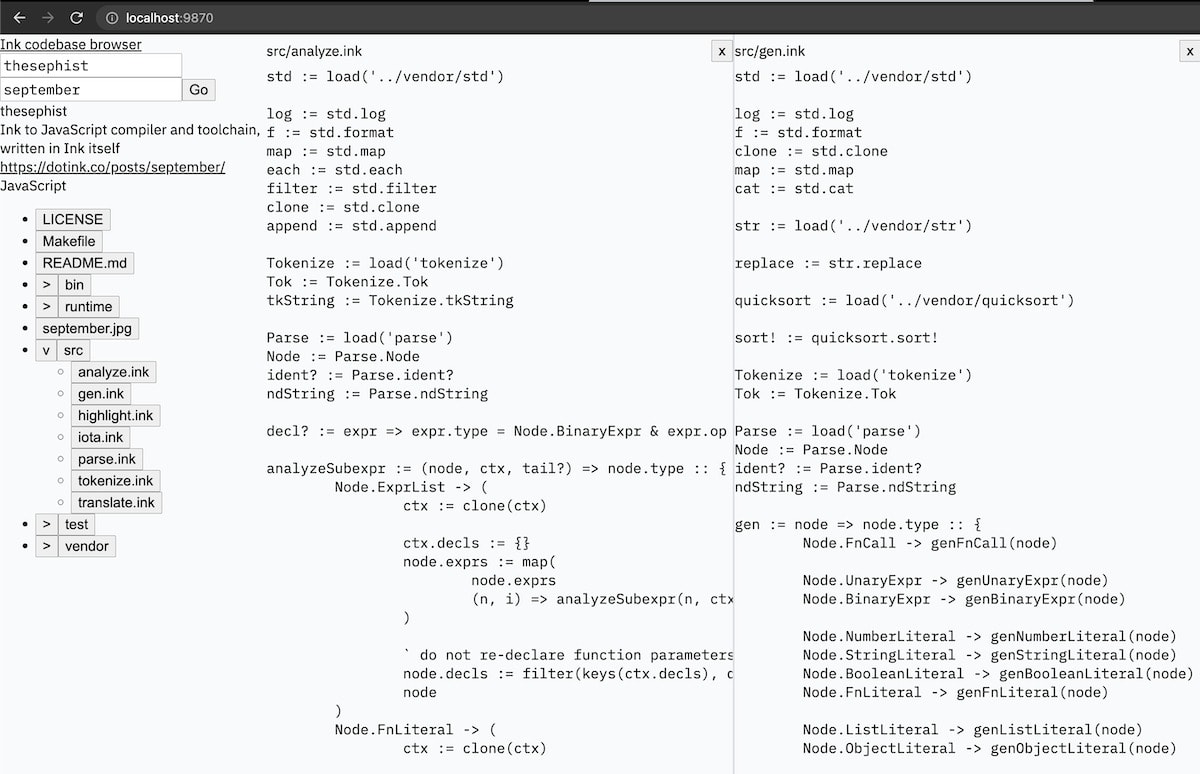

While this is crude, it was enough for me to validate that an interactive file tree sidebar like this could work for me. Next, I started building a way to open files. All I really cared for at first were source code files, which are text files. So the next screenshot shows a version of the app where clicking on any file would download the contents of that file from the API and dump it into a <pre> tag on the right side of the page.

At this point, I had a skeleton of my app starting to emerge. Even though it looked sloppy and had a few bugs, it could navigate me to a GitHub repository and let me open multiple files at once from a hierarchical file tree – meaning it did its job, and was already somewhat more useful than GitHub’s own interface already!

Getting the “code editor” feel

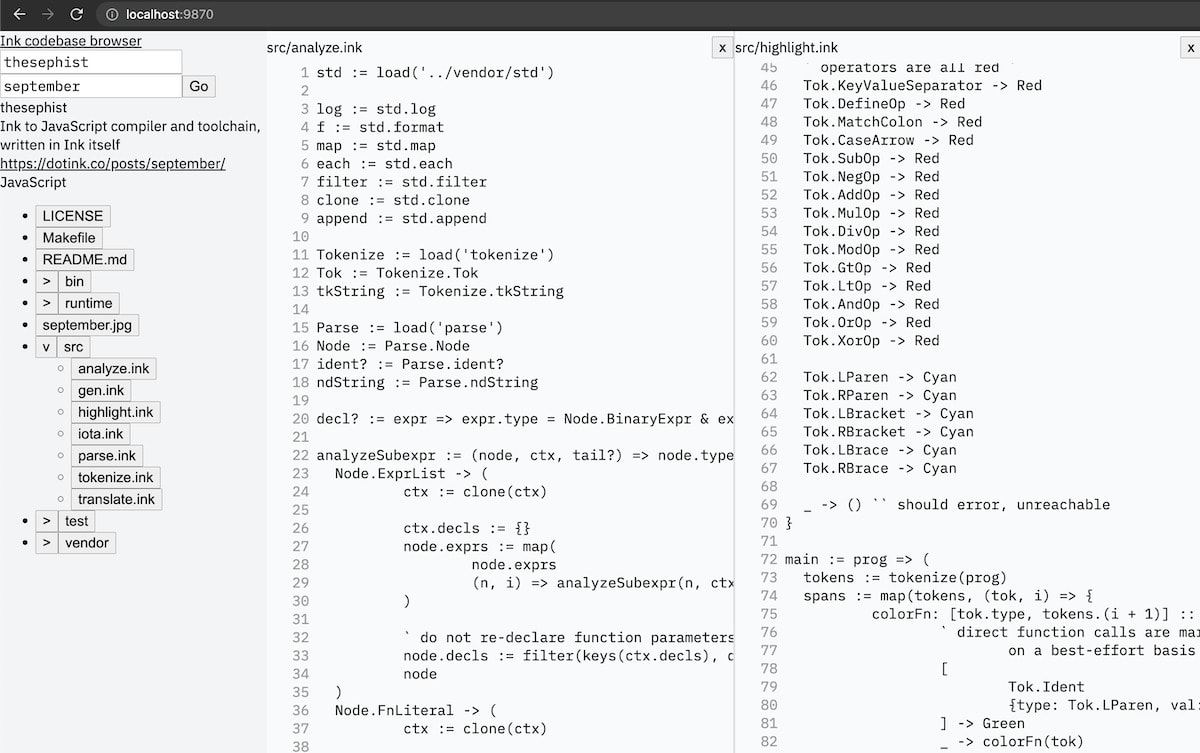

My next round of work focused on making the source code previews more hospitable. First, I needed line numbers next to each line of code. This took me two attempts to get it right. First, I tried to divide up the source code into lines, and then make one <div> per line that included the line number and the code itself. This worked okay, but had two issues:

- If I wanted to copy multiple lines of code from the preview, I would also inadvertently copy the line numbers, which I almost never want to copy.

- Syntax highlighters need a single contiguous block of text to syntax-highlight, and will often deliver inconsistent or buggy results because of parsing errors if the code is sliced up into lines.

There are possible workarounds for both of these issues, but I elected to instead find a simpler solution: A single long and skinny <pre> for line numbers on the left, and another long <pre> for the code, spaced out just right so they line up with each other.

Next up, I reconsidered the split-pane design from my first attempt above. Initially, I wanted to see if simply having panes without tabs could work. In that approach, opening a new file would simply add a pane to the right of other open panes. But the more I played with my existing prototype, the more I realized I would probably eventually want each pane to have a few tabs I could switch between. So rather than push it off, I decided to re-design the code to support tabs inside panes.

My “open files” state went from a list of files…

panes: [

{ file object }

{ file object }

{ file object }

]

… to a list of panes, each of which contained files.

panes: [

[ { file }, { file } ] ` 1st pane `

[ { file }, { file }, { file } ] ` 2nd pane `

]

And as a result, all new files now opened in a single pane, in tabs!

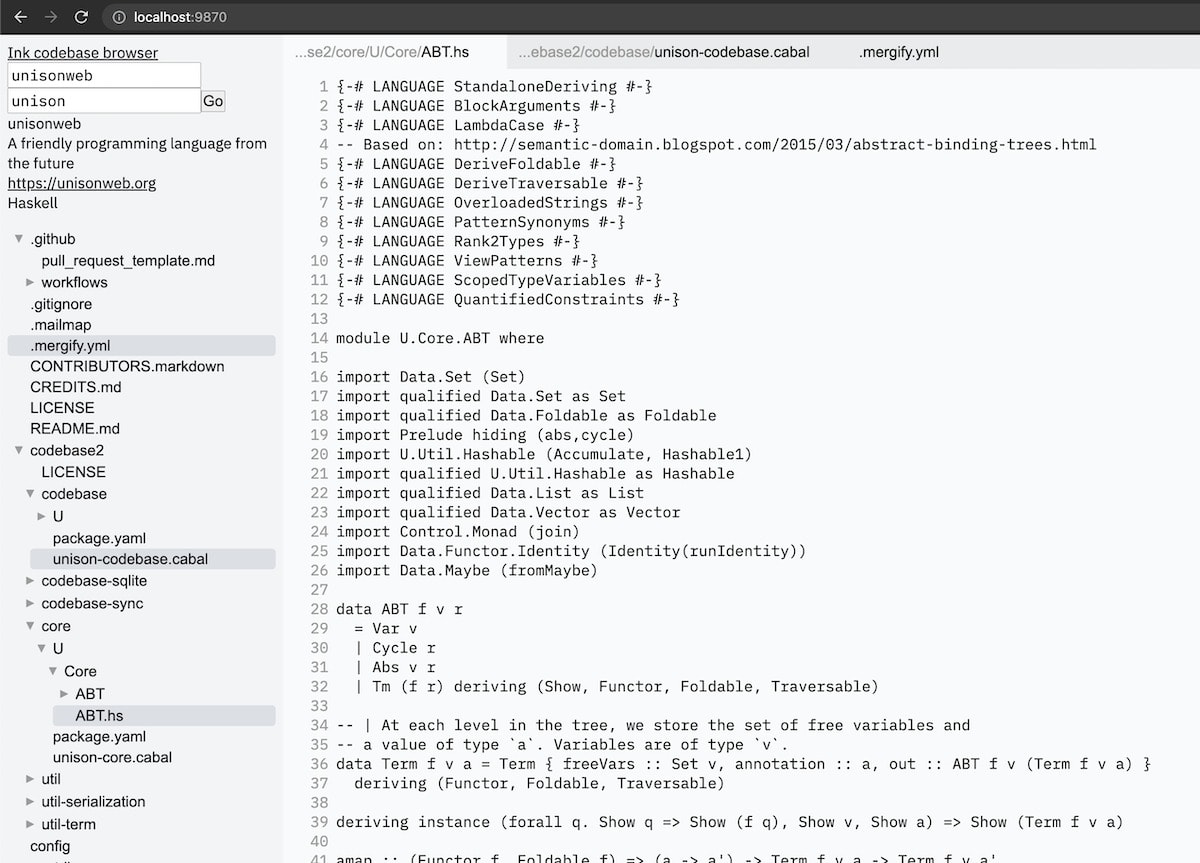

These tab buttons were an eyesore, so I added a bit of CSS to make the tabs look more natural and appealing. (The example codebase below is from the Unison programming language.)

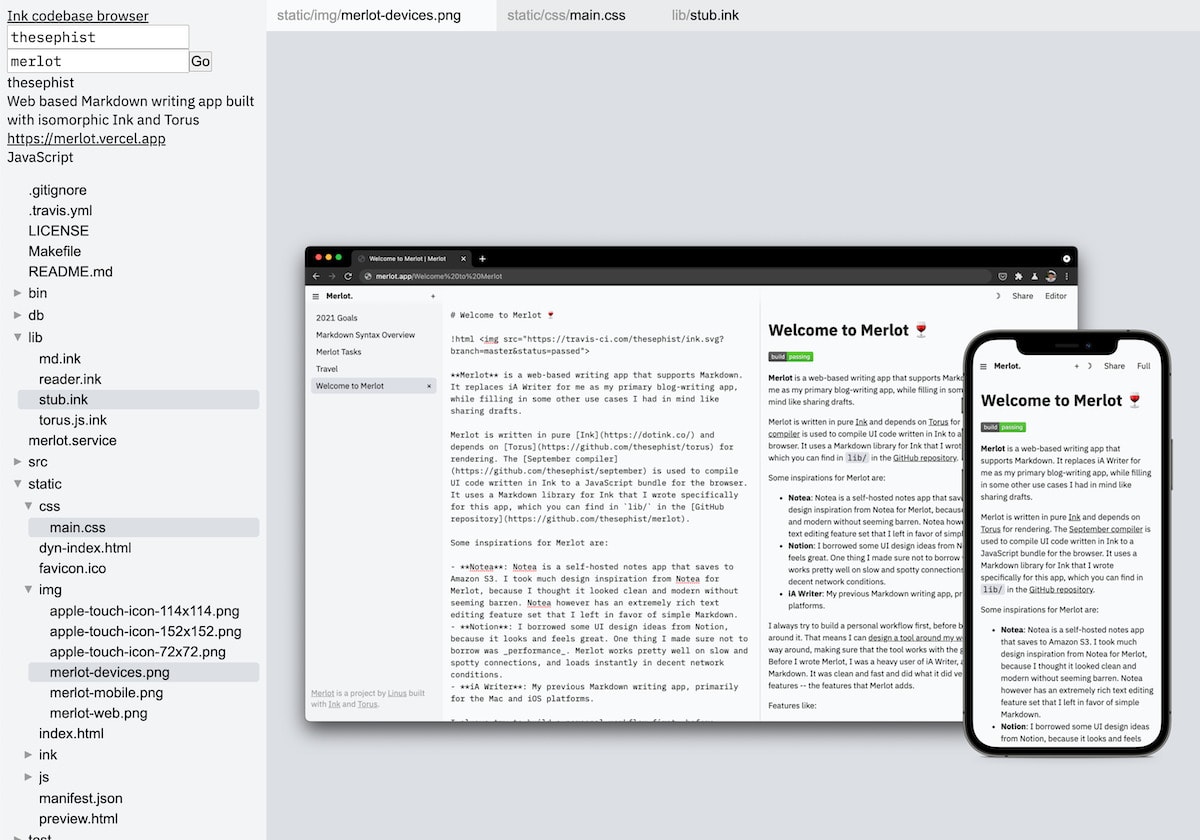

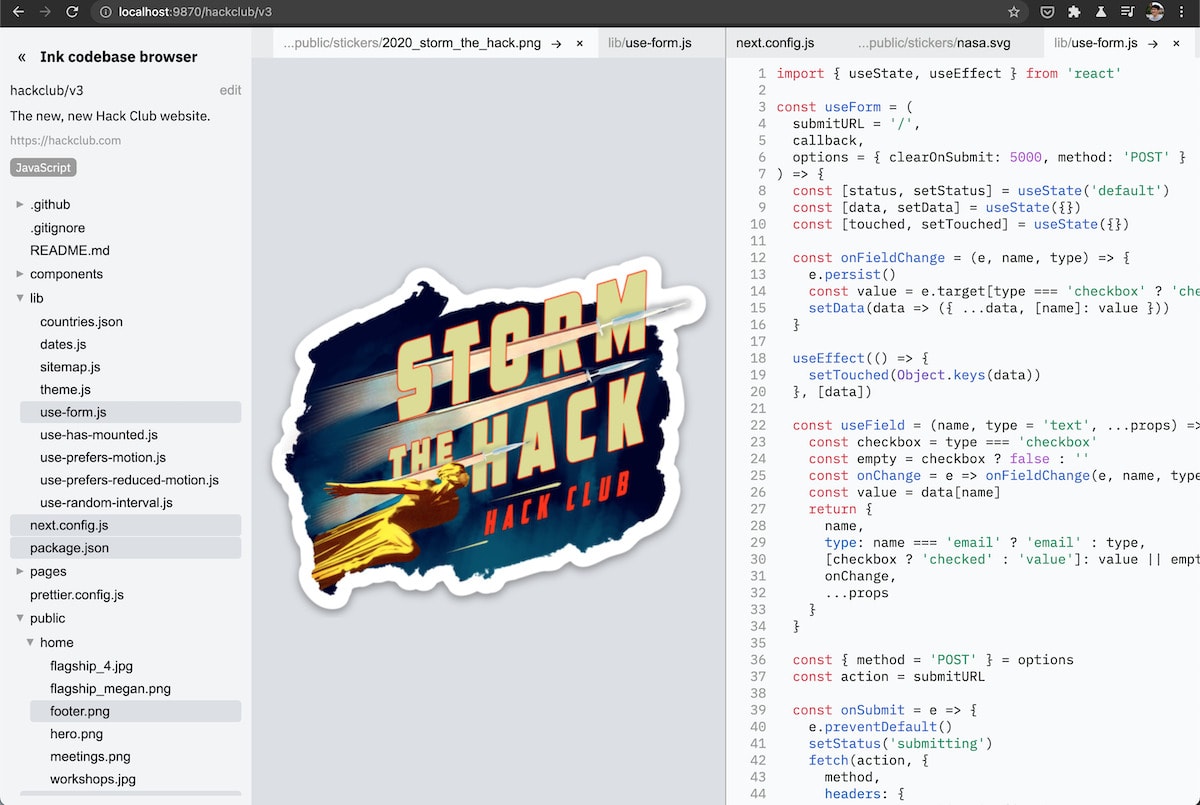

When I began to test my code so far with example repositories, I kept accidentally opening non-text files like image files. This was an issue, since my code assumed up until this point that every file was a text file that should be displayed as text. To stop myself from running into this issue over and over, I added support for image previews for files that had common image format file extensions like .jpg and .png.

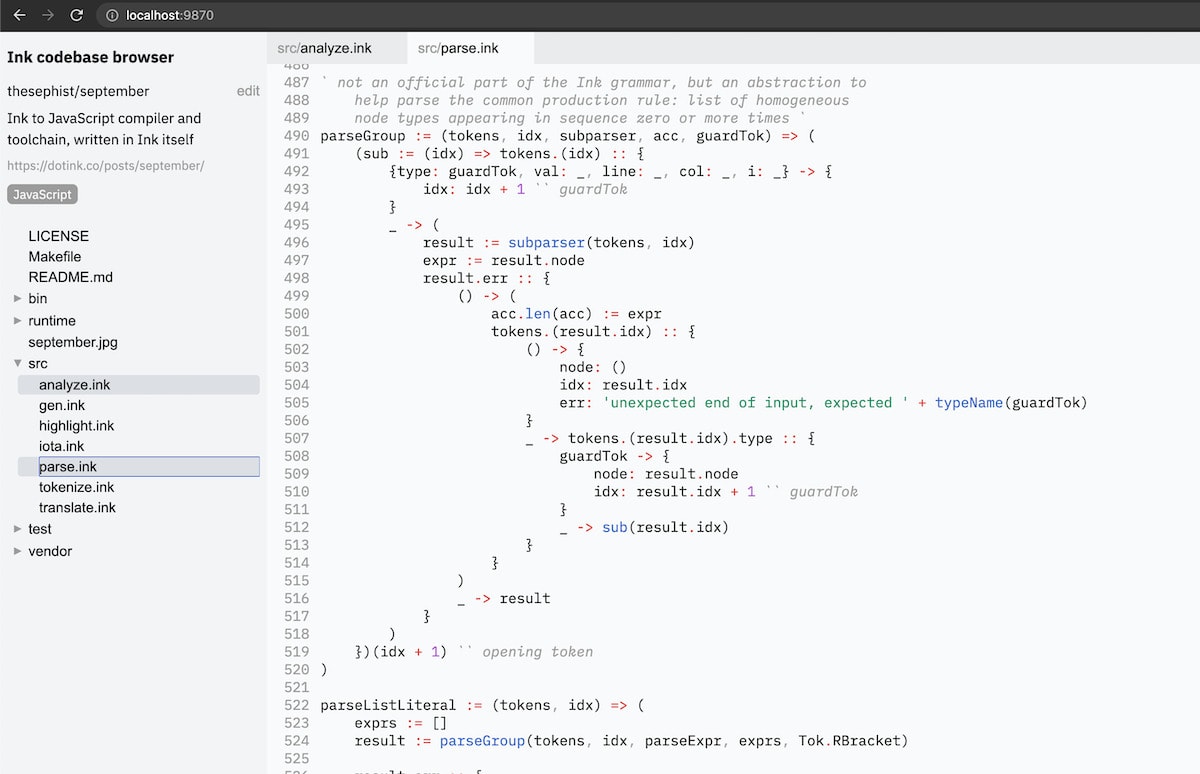

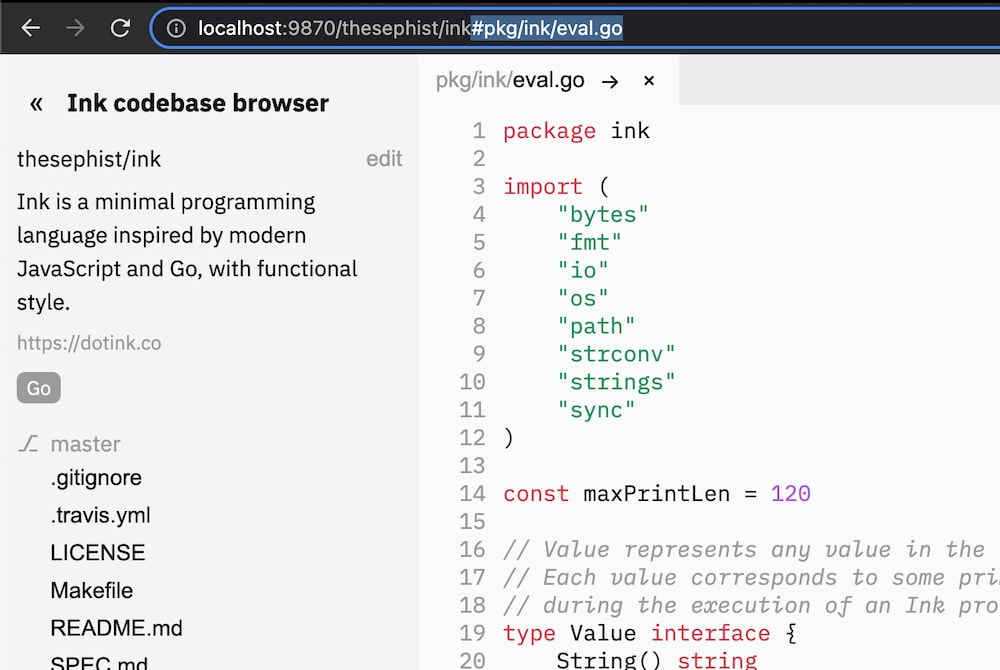

Adding syntax highlighting

One of my important goals with this project was to make ICB a genuinely better experience for browsing codebases than GitHub. And to hit that goal, ICB was missing one critical feature for me: proper syntax highlighting for most common languages. So that’s what I tackled next.

I needed two different syntax highlighting strategies, one for Ink programs (for which there’s really only one solution) and one for all other popular languages. I chose to use highlight.js for highlighting common languages, because I’ve used it before in the Litterate documentation generator project. As for highlighting Ink code, I knew that the syntax highlighter from the September toolchain could be modified to generate HTML (rather than terminal) output, because Andrew Healey had achieved it for the Ink by Example project. So I decided to take that approach. Both highlighters would run on the client-side, in the browser.

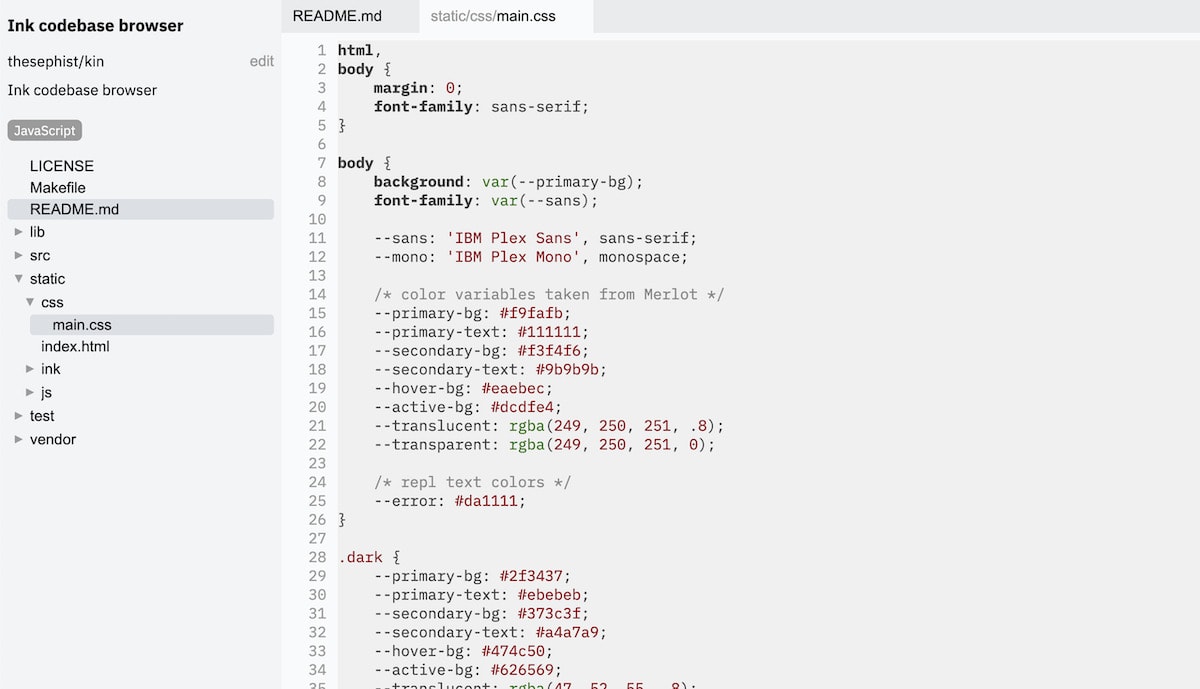

First up, I added highlight.js’s syntax highlighting. Here’s a CSS file highlighted with the default theme.

That’s easier to read, but now the colors don’t match! That’s ok – I would correct this later by matching the highlighting colors to the color theme of the rest of the app. Next up, I compiled September’s syntax highlighter to JavaScript to add highlighting for Ink source code.

With colors corrected, the syntax highlighting looked much better.

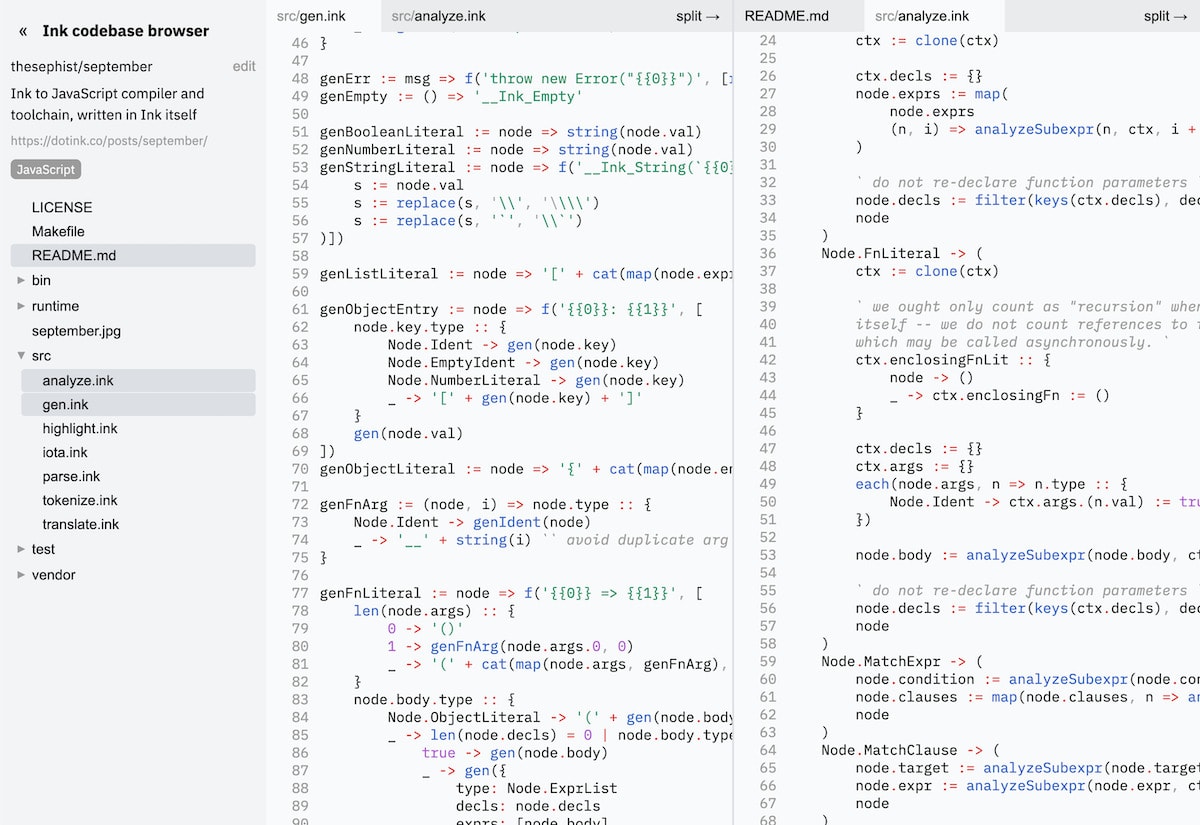

Panes, tabs, and splits

Until this point, the app only supported opening new files in a single pane with multiple tabs. With most of the core features proven out, I wanted to return to pane and tab organization and improve this situation.

I thought for a while on the fastest way to add support for panes. Most real IDEs allow you to drag and drop tabs anywhere on the screen to split panes into multiple panes or move tabs around, but writing a full drag and drop split-pane system in Ink seemed like a tall order, and I wanted to wrap up a first version soon. So, instead, I came up with a hacky solution that still made panes very usable: In this revision, the currently open tab got a “split →” button to “send this tab to the next pane”.

Clicking the “split →” button opens that specific file in the pane that’s to the right of the current pane. If one doesn’t exist, a new pane is split off from the old one. This is a little clunky, but I found that I could get basically any kind of arrangement I practically needed by opening files in the first pane and sending them to other panes with a few clicks.

Eventually, that button was incorporated into the design of the active tab itself. It took up less horizontal space on the tab bar, and I felt it was more representative of what was actually happening – the button splits a tab, not a whole pane.

After some experimentation, I decided this was sufficient for me to move on.

Finishing polishes

I hadn’t anticipated adding Markdown preview support, but once I started browsing real repositories, I found many repositories (including most of mine) where the README held important information, but wasn’t very readable in source-code format because of text wrapping and other issues. Since I had already written a Markdown engine in Ink called Merlot, I decided to just use it to render Markdown file previews. Merlot isn’t GitHub Markdown-compliant, so it frequently misses images or inline HTML code, but for the most part it does the job.

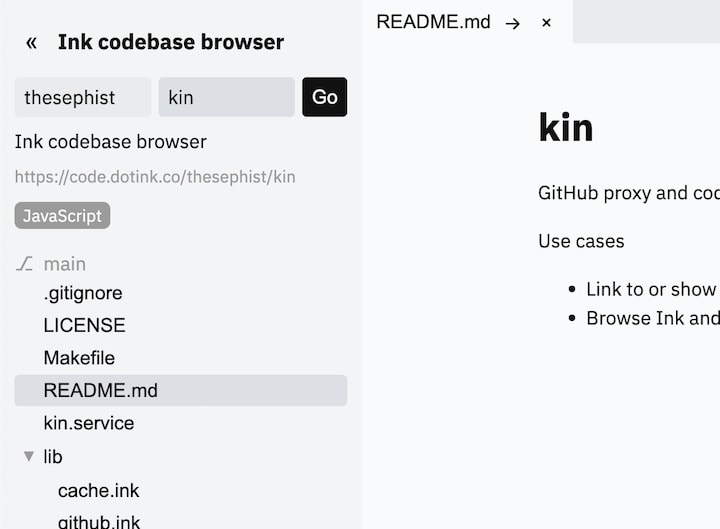

I finally spent some time cleaning up the interface around navigating to a new repository.

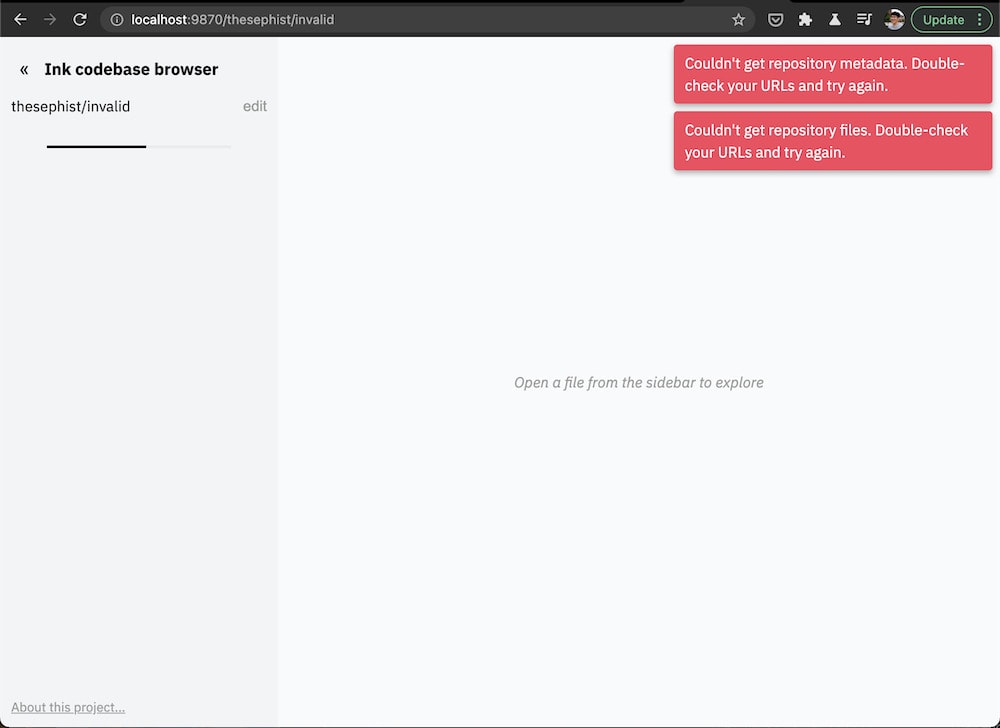

Good error handling is important, and until this point, navigating to a nonexistent or private repository simply left the app hanging in a loading state. To improve this, I added some error alert boxes to the interface that pop up whenever something fails over the network.

Lastly, I used the built-in router API from my Torus library to let anyone deep-link to a specific file in a specific repository using the URL. For example, this link directly opens the React Hooks file in the React repository.

The final product

After some final debugging work and small UI touches for mobile, we had a version one! I set the default repository to be the now-public repository for the Ink codebase browser itself, and released it into the public.

Altogether, the ICB project took about three days of hacking on the side from zero to where it is today. It’s probably the most complex piece of UI I’ve written so far with Ink, and the project with the most sophisticated set of dependencies. In addition to developing some new tricks for organizing Ink code (especially UI code) in this project, I’m starting to realize I probably need to give Ink a proper package registry and manager. So perhaps that will be my next.

← Ink playground: the magic of self-hosting a compiler on JavaScript

Optimizing the Oak compiler for 30% smaller, 40% faster bundles →