Contents

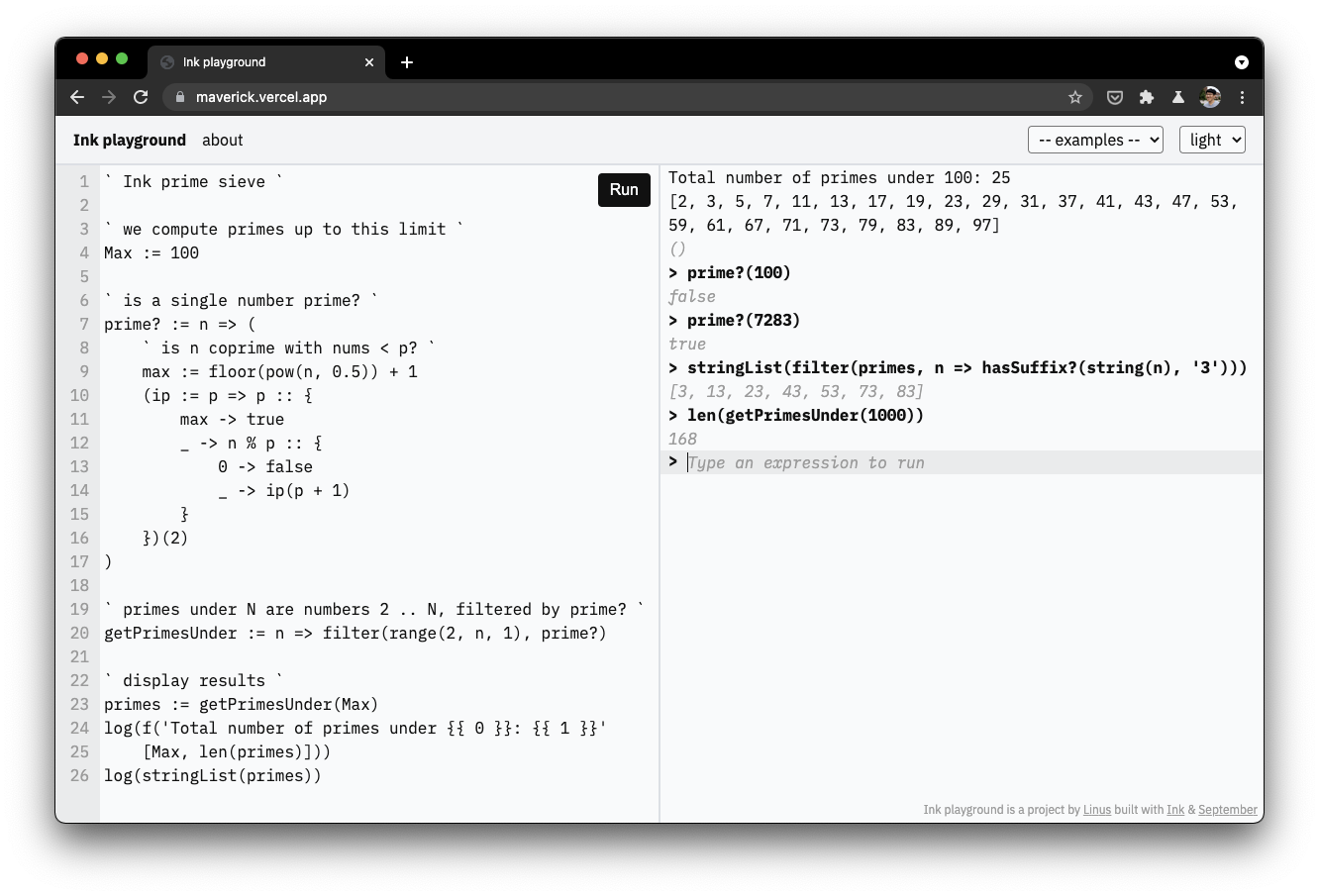

The Ink playground, named project “Maverick”, is a web IDE and REPL for Ink. It’s a single-page web application written in pure Ink, and makes it possible to write and run Ink programs entirely in the browser.

With the playground, we can program in Ink on the go on a mobile device, or on a system that doesn’t have Ink installed. It also allows me to embed an Ink programming environment directly into a website or blog, like this.

See on GitHub Try Ink playground →

There’s quite a bit of fun technical magic that enables us to compile and run Ink inside a web browser, and I want to dig into this a bit in this blog.

A web IDE and REPL for Ink

When I first started writing Ink programs, I wanted a way to experiment with Ink in a browser-based programming environment. I wanted to write Ink code when I wasn’t sitting at my laptop, when I was outside. I also wanted to be able to fire up little coding experiments from my iPad on the couch without having to set up a whole new file or project on my computer.

My first solution was a browser-based REPL, where the browser would send Ink programs I wrote to a backend evaluation service to be executed. The backend service was built with Node, and for every evaluation request, it spawned an Ink child process to run the program and gather the output to send back to the browser.

This worked alright, but had some major downsides.

- It depended on a solid connection to a backend evaluation service, which isn’t always available and adds latency to every run, and which I would have to maintain.

- It couldn’t stream the output from the program back in real-time. There are solutions to this – for example, we could use a WebSocket connection between the server and browser to stream the output of the child process in real-time to the client. But I didn’t want to deal with the added complexity.

- The architecture meant anyone could execute arbitrary code on my backend, including things like sending it into an infinite loop. Even with Ink’s permission system, I didn’t feel great about this.

Given these downsides, at the time, I didn’t launch this REPL prototype or make it widely available.

A little while later, I built September, a compiler that can transform Ink programs to equivalent JavaScript programs. The original purpose of September was to let me run Ink programs in the browser, so I could write front-end applications in Ink. But recently, I had an interesting idea.

September is written in Ink. Could we compile September using itself, to get an Ink compiler that runs in the browser? And if we can do that, could we use that to make an Ink REPL that runs entirely in the browser, without needing a backend?

Self-hosting an Ink compiler in JavaScript

The September compiler is written entirely in Ink, and self-hosting (compiling the compiler with itself) was one of the goals of the project from the beginning. I knew it was probably possible, but hadn’t had a reason to attempt it until this idea came to me.

September’s compiler has two completely separate parts: the part that reads the command-line arguments, reads files from disk, and handles any errors; and the “translation” function that performs the actual compilation, taking Ink source code as input and returning JavaScript source code.

To begin, I simply gave all the source files belonging to the translation part of the compiler to itself, and stuck the result into the browser. This was as simple as

september translate \

../september/src/iota.ink \

../september/src/tokenize.ink \

../september/src/parse.ink \

../september/src/analyze.ink \

../september/src/gen.ink \

../september/src/translate.ink \

> static/ink/september.js

Then I wrapped the compiler’s main function in a JavaScript function called translateInkToJS, and after fixing a couple of scoping bugs in the compiler, we had the compiler running in the browser!

> translateInkToJS('1 + 2 + 3')

'log(__as_ink_string(__as_ink_string(1 + 2) + 3))'

The output of the compiler here is still simply a string containing JavaScript program. To keep things simple, I chose to run these resulting programs through JavaScript’s eval(), which returns to us the result of evaluating a given JavaScript program.

> eval(translateInkToJS('1 + 2 + 3'))

6

We have made Ink-JavaScript contact! We can now compile and run Ink programs entirely in the browser.

I spent some more time running more complex Ink programs through the (now web-based) compiler to ensure things worked correctly, and then building a simple UI around it using the CodeMirror text editor and Torus.

Running Ink programs in the browser

At this point, we have an Ink compiler, compiled with itself, running in the browser and compiling other Ink programs. In other words, the language bootstrapping chain is:

Ink interpreter (written in Go)

--(which runs)-> September compiler (written in Ink)

--(which compiles)-> September compiler (to JavaScript)

--(which compiles)-> other Ink programs (from Ink, to JS)

--(which runs in)-> JavaScript's eval() function

--(which returns)-> the result!

That’s quite a compiler rabbit hole. But simply compiling Ink programs to JavaScript in the browser isn’t the end of it. To have a full Ink programming environment, we need to get a few more things working.

First, most Ink programs require the standard library, at least the std (standard library core), str (string functions), and quicksort (list sorting) libraries. Fortunately, these three libraries are also dependencies of the compiler, so they were already compiled into the JavaScript bundle and available as global variables in the browser. This meant Ink programs running in the playground can simply call, for example, sort!([1, 3, 2]) without having to import other libraries.

Second, many Ink programs we could run in the playground resulted in errors. When an error occurs, the eval() function would simply propagate that error through to the surrounding application, causing the playground to crash. We obviously don’t want this, so rather than calling eval() directly on the compiler output, I updated the code to evaluate something like

eval(`

try {

${translateInkToJS(...)}

} catch (e) {

// render the error to the REPL

}

`)

This meant, if an error occurred in the compiled program (for example, if a variable was undefined), the error would be caught and displayed in the REPL rather than propagate up to the rest of the playground app.

Lastly, there are some quirks to the fact that the playground runs the compiler in a new environment. September’s parser and compiler isn’t designed to process completely untrusted input, because it was originally meant to compile Ink programs that ran correctly using the native interpreter. So September sometimes errors and crashes on blatantly incorrect Ink programs. Because the compiled Ink program runs in the same global scope as the rest of the playground app, an Ink program may also modify the surrounding app state in strange ways. For example, defining a variable named Math in Ink will crash the playground, because it conflicts with JavaScript’s built-in Math object.

Some of these issues I chose to keep as acceptable quirks of this environment, and others (like compiler crashes) I’m hoping to fix slowly going forward.

I’m very excited to have a browser-native REPL for Ink for experimenting with Ink on the go, and for writing and testing small things in Ink in a more lightweight environment. Though it obviously isn’t perfect, it’ll also help me demonstrate how Ink works in more places around the web and make the language more accessible to people who are interested in trying to write small Ink programs.