Contents

Ink is a mostly functional programming language, and Ink programs express iteration through recursion. Usually, this kind of recursion is hidden behind higher level library functions like map and each. But under the hood, all loops and iteration in Ink makes use of recursive functions.

For example, the standard library’s std.each function for looping over elements of a list is defined with an inner function sub that recursively calls itself.

each := (list, f) => (

max := len(list)

(sub := i => i :: {

max -> ()

_ -> (

f(list.(i), i)

sub(i + 1)

)

})(0)

)

To use recursion for looping like this, Ink requires that the runtime environment that runs Ink support tail call elimination, which prevents long loops from overflowing the stack. The main Go-based interpreter for Ink has supported proper tail calls since its inception to allow arbitrary-depth loops and recursion, but the Rust-based bytecode VM and JavaScript compiler for Ink, called September didn’t have support for proper tail calls until recently.

Different compilers and interpreters implement tail call elimination differently, and even between Ink’s various implementations, there are differences that impact what kinds of programs we can run on each.

The rest of this post explores tail call elimination, how compilers implement it in the wild, and how I managed to add it to Ink’s interpreters and compilers by looking at some real implementation code. In my research, I stumbled across lots of resources about what tail call elimination is, but very few references on how different runtimes and languages implement it. So I’ve also included a broad survey of methods for the current pantheon of programming language runtimes in this post.

"Tail calls" but instead of it being a compiler/PL term it's booty calls but for things with literal tails

— Linus (@thesephist) February 7, 2021

Tail call elimination and Ink

(If you’re familiar with TCE, feel free to skip to the next section)

As a quick review, tail calls are function calls that occur as the last thing in a function. In other words, if the thing that a function returns is a call to another function, that call is called a “tail call” because it’s in the “tail position” of the function (meaning it’s the last thing in the surrounding function).

Tail calls are not always recursive. For example, here, b() is a normal non-recursive tail call, and a() is a recursive tail call, because it calls itself. But in either case, calls to a() and b() are the last things that happen in that function – they are returned from the parent call to a(), so they’re tail calls.

a := () => check?() :: {

true -> a()

false -> b()

}

In language runtimes without tail call elimination (TCE), a function that loops by recursively calling itself might blow up the call stack if the list is too long, because it’ll call itself too many times and exhaust memory. But if we know that e.g. the sub(i + 1) call in the std.each implementation at the top of this post is the last thing that happens in the function, we can throw away the memory we used for the current call of the function right before the recursive call, and reuse that space we just reclaimed to evaluate the new call to sub.

This is, in essence, the benefit of TCE. It allows tail recursion not to blow the call stack by reusing the same space in memory for each “loop”, and sophisticated compilers can transform tail recursion into normal, efficient loops. However, it’s important to realize the primary purpose of TCE isn’t speed, but memory efficiency.

Ink relies heavily on the compiler or interpreter transforming tail calls into these space-saving recursive calls. Unlike other languages that have loop syntax or a recur construct to loop explicitly, all loops in Ink are written as recursion (a bit of lazy design by me when I wrote the language that’s proven elegant). Without proper TCE for these kinds of looping recursions, most Ink programs will quickly explode the call stack and crash. Ink programs compiled to JS with the September compiler crashed when looping more than 1000 times until the recent addition of TCE support for this exact reason.

By the way, computer scientists are bad at naming

There are a few different concepts with “tail-” in the name in the programming language world, and they seem to confuse folks. So before we dive into implementations, let’s clear up the difference between tail calls, tail recursion, tail call elimination, and tail call optimization.

A tail call is simply a name for a function call that happens in the tail position, as the last thing in a function (as the return value).

Tail calls are frequently used to implement looping and iteration in functional languages. When a tail call in a function is a call to itself, it implements looping via a recursive call. We call this kind of recursive tail call tail recursion, and we say that this function is tail recursive.

Tail call elimination is a feature of programming languages and runtimes (compilers and interpreters) that ensure that tail calls use constant stack space, and don’t blow up the stack on long chains of recursive tail calls. TCE is useful and often required for languages using tail calls to loop, like Ink. Some environments or projects will call TCE by another name, like proper tail calls (PTC). As far as I can tell, TCE and PTC refer to the same thing, with PTC sometimes preferred because it tends to get confused less with these other words here.

Many languages like C and Java don’t need or don’t want to support tail call elimination, but there are still performance benefits they could get by selectively eliminating certain kinds of tail calls into simpler constructs like jumps or loops. This is a kind of optimization certain compilers perform, and it’s called tail call optimization. The most important difference between TC elimination and TC optimization is that we use “elimination” to mean that TCE is guaranteed, and “optimization” to mean that it’s an optional optimization and not guaranteed by the language or compiler.

TCE techniques in the wild

Tail call elimination really happens at the interface boundary between tail-call-looping languages like Ink and languages that have more traditional for/while loops like Go, C, or even machine hardware. TCE isn’t necessary between languages that require TCE, or between languages that don’t care for tail calls. We can think of TCE as a way to transform one way of expressing control flow into another way of expressing control flow: function calls to jumps or loops.

In the wild, there are a few different languages and compilers that support TCE to varying degrees. Most of these implementations take one of a few popular approaches to do this transformation work. Let’s look at them in order.

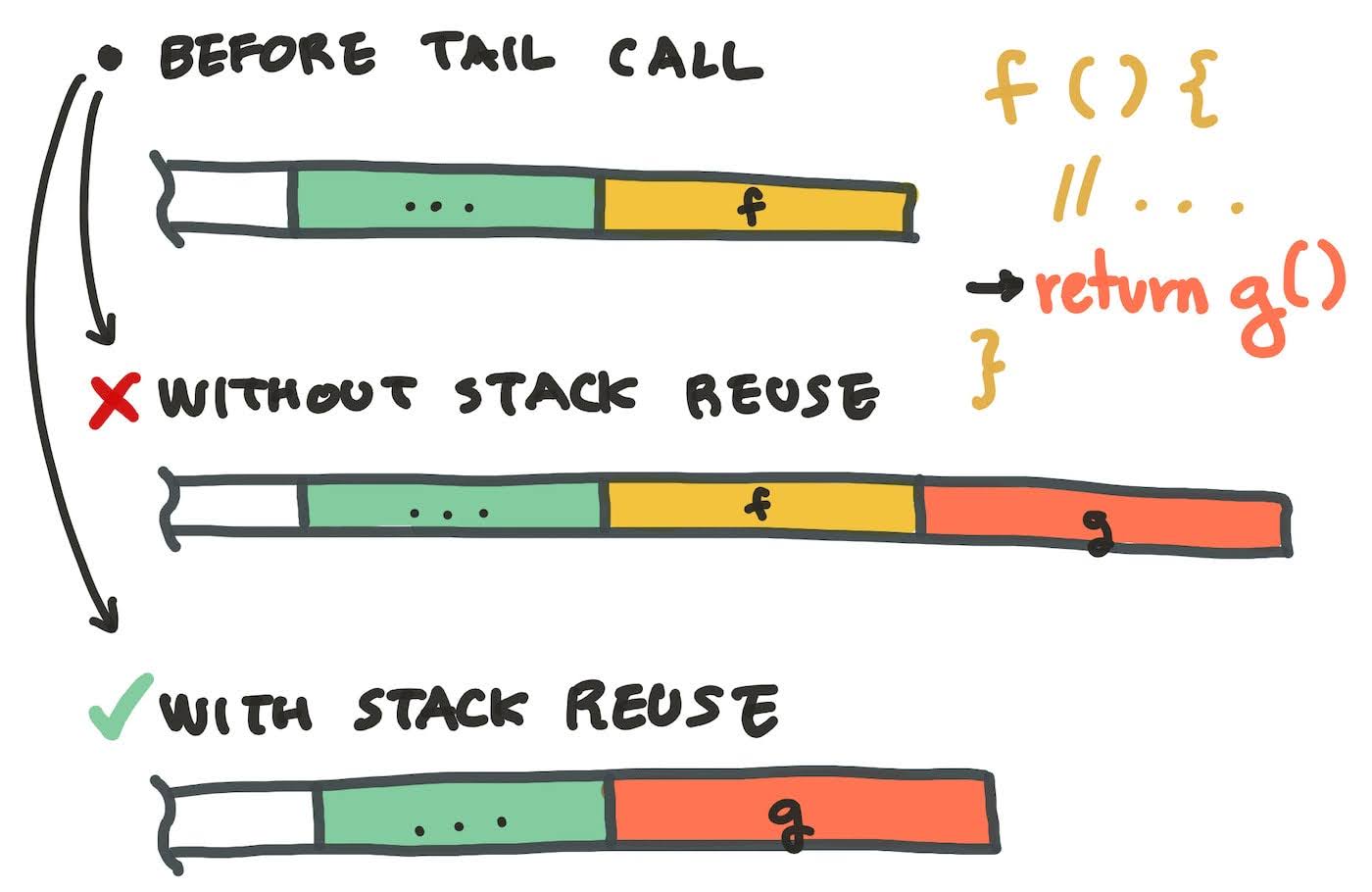

Stack reuse

Stack reuse is an efficient way to implement TCE for tail recursive functions. It performs TCE by compiling the tail recursive function so that a recursive tail call reuses the current space in the call stack for the new function call, rather than allocating a new stack frame. However, stack reuse usually comes with the constraint that the return value (and sometimes arguments) to the caller and callee functions must match. (In dynamically typed languages, this constraints disappears because there’s just one type, the “everything” type.)

You’ll also frequently hear this method referred to as TCE “using a goto”. Some languages implement tail recursion by turning

fn foo(x) {

...

return foo(x + 1)

}

into a

fn foo(x) {

...

x = x + 1

goto start of function

}

during compilation, which effectively “reuses the current stack” for the new function call. At a high level, TCE using a goto and TCE by reusing the stack do the same thing.

WebKit’s JavaScript engine (in Safari and iOS devices) implements TCE using this method, but only under strict mode. WebKit refers to this as “proper tail calls” (PTC). JavaScript is technically specified to support TCE everywhere, but most browsers don’t follow the specification here for a myriad of reasons.

Stack reuse is also used by Lua, and it’s the way some C compilers like LLVM/clang implement TCO (meaning they don’t apply it everywhere but selectively use it as an optimization).

Transformation into loops

To perform stack reuse in TCE, the language runtime needs to have fine-grained control over the call stack of the programming language to jump to arbitrary points in the stack. Many environments like JavaScript and the Java Virtual Machine don’t allow a programming language runtime to directly manipulate the stack like this, so languages have come up with the next-best option, transforming tail recursion into loops. This technique comes with the same constraint as stack reuse – return types must match between callers and callees.

Tail recursion is usually used to emulate loops, unless you’re doing something more funky and special like continuation-passing. In these use cases, tail recursive functions often look like this, where the function checks some condition, and tail-calls itself in a conditional branch with a new value for the arguments.

function compute_something(x):

do_some_work(x)

if some_condition:

return x

else:

return compute_something(x + 1)

This kind of tail recursion can be re-written to a loop! This particular function might be re-written to be:

function compute_something(x):

loop:

do_some_work(x)

if some_condition:

return x

else:

x = x + 1

continue loop

Smart compilers can detect tail recursion in a conditional statement like above and transform it to an equivalent loop like below. As you might guess, not all tail recursion takes this form (for example, mutual tail recursion can’t be rewritten as loops). This means this loop transformation technique can’t eliminate every tail call. Still compilers frequently use this technique to take care of tail recursion where it really matters, like in loops and iterative algorithms.

The Clojure and ClojureScript compilers use this technique to unroll recursion into loops to run on non-TCE’d platforms like the JVM and JavaScript. I suspect many other compile-to-JavaScript languages will use a similar technique.

Trampolines

The previous two techniques have the advantage that they’re usually as efficient as their equivalent loops, but they have the downside that they can’t account for all kinds of tall calls, only “self recursion” or tail calling functions that recursively call itself. Many languages like Scheme require all tail calls to support TCE, and some programming patterns also require proper TCE everywhere. To support these cases, we can use a trampoline.

To use a trampoline, we take our tail-recursive function

function compute_something(x):

do_some_work(x)

if some_condition:

return x

else:

return compute_something(x + 1)

compute_something(3)

and transform it to something like

function compute_something(x):

do_some_work(x)

if some_condition:

return x

else:

return make_trampoline(compute_something(x + 1))

function unwrap_trampoline(result):

while result is a trampoline value:

result = evaluate result

return result

unwrap_trampoline(compute_something(3))

In a trampoline setup, a recursive tail call returns a “trampoline” value that represents some function to call with some arguments, but doesn’t actually call it yet. When you call a trampolined function properly (with unwrap_trampoline here), the unwrapper function will use the trampoline value returned by the called function (compute_something in this case) to keep calling it in a loop until the thing it returns is no longer a trampoline value.

I sometimes think of this method as “unwrapping the recursion into a while loop” because the actual “recursive call” now happens in a while loop that “trampolines” function calls until all tail calls are complete.

Trampolines have two obvious downsides:

- Trampolines need to be written into the program, either manually or by the compiler, and it changes the function into something it originally wasn’t (because now it sometimes returns this weird “trampoline value” thing). It’s an intrusive transformation.

- Unlike the two options we’ve looked at previously, trampolines add measurable overhead to function calls that use it.

Despite the downsides, sometimes a trampoline is the best way to achieve or emulate tail recursion, so many languages have some construct that allows you to use trampolines, like the tramp Rust crate, the clojure.core/trampoline function in Clojure, and many other lower level languages.

The advantage of trampolines is that it can emulate TCE for any tail recursive function call, including tail calls that aren’t recursive, or calls that don’t have matching types.

Other noteworthy TCE techniques

Haskell uses a unique graph reduction computation model, which obviates the need for explicit “tail call elimination” for sake of performance or memory overhead. Haskell still supports tail call optimizations, but its use case is much different from the ones we explored here.

Variants of Scheme support TCE by specification. Chez Scheme uses its excellent support of continuations to implement tail recursion. Chicken Scheme uses a novel approach, where each function calls checks the total stack size used, and if it exceeds some limit, it garbage-collects values no longer needed in the stack and moves the rest of the variables in the stack to the heap. In effect, this emulates tail call elimination because tail recursive loops won’t blow the stack.

Implementing TCE for Ink

Ink doesn’t have a specification that requires that all tail calls be eliminated away, but to have a useful Ink runtime, recursive tail calls must be eliminated at the very least, because that’s how Ink programs loop. Ink has three runtimes today: the main interpreter written in Go, an experimental (partially complete) bytecode VM in Rust, and a compiler to JavaScript written in Ink itself. Each runtime needed a TCE implementation of some kind.

All three implementations currently use variations of the techniques we looked at above.

The main Ink interpreter

The main Ink interpreter is written in Go, and is a tree walk interpreter. This means the Ink program is parsed into a syntax tree, and a simple evaluator walks the nodes of the syntax tree like “function”, “expression”, or “variable” to evaluate the program according to its rules, as the program was written.

The benefit of this design is that the interpreter becomes super simple. There are no compilation or transformation steps in the interpreter for sneaky bugs to creep in, and all the logic is trivial to check. Modern computers are quite fast, so this turns out not to be too slow for most programming tasks, either.

On the downside, the constraint of this design is that there is no explicit “compile” step at which the interpreter could transform a tail call into something more efficient like a loop with an exit condition. Ink doesn’t have the concept of a loop at all, so the interpreter can’t transform tail recursion into anything simpler.

Because of this, the Go interpreter uses a trampoline in the runtime to emulate tail call elimination. Every tail call returns as a trampoline value called a “thunk” that represents the function to be called, and the caller checks if a return value is a thunk to “unwrap” it as required.

You can see this in action in the Go code that calls into Ink functions:

// pkg/ink/eval.go, line 769

func evalInkFunction(fn Value, allowThunk bool, args ...Value) (Value, error) {

// ... prepare function call

// TCO: used for evaluating expressions that may be in tail positions

// at the end of Nodes whose evaluation allocates another StackFrame

// like ExpressionList and FunctionLiteral's body

returnThunk := FunctionCallThunkValue{

vt: argValueTable,

function: fnv,

}

// allowThunk == true if in tail position

if allowThunk {

return returnThunk, nil

}

// otherwise, return an unwrapped, real value

return unwrapThunk(returnThunk)

// ...

}

Although this adds some overhead to recursive tail calls, the benefit of the simple interpreter design and safe tail recursion makes it worth the tradeoff.

Schrift, the bytecode VM

Schrift is a Rust-based bytecode VM interpreter for Ink. It’s still in an unfinished state, but the interpreter supports almost all core language features, including reliable tail call elimination.

The main difference between Ink’s Go interpreter and Schrift is that the Go interpreter uses Go’s native call stack as Ink’s “call stack”, while Schrift creates an explicit call stack for Ink code. In other words, when the Go interpreter calls a function, it simply calls a corresponding Go function under the hood. Schrift, by comparison, keeps an explicit “call stack” data structure in memory for Ink bytecode where all stack variables and function calls live. This means Schrift can manipulate the stack with more control than the Go interpreter, and true tail call elimination with stack reuse is possible.

When the Schrift VM arrives at a function call in the tail position, rather than adding onto the existing call stack, the VM replaces the caller’s stack frame with the callee’s stack frame and jumps back to the top of the VM’s execution loop.

In practice, as you can see in the Schrift VM source code here, the stack “reuse” is done by popping the last stack frame off and pushing the new stack frame onto the call stack. This takes some inspiration from Chicken Scheme’s approach, and avoids the “argument and return types must match” restriction of pure stack reuse. With this method, all tail calls get the benefit of TCE.

// src/vm.rs, line 337

// end of VM execution loop

// maybe_callee_frame is the stack frame for

// a function that needs to be called next.

match maybe_callee_frame {

Some(mut callee_frame) => {

// should_pop_frame() is true if we're

// in a tail position of a function

while self.should_pop_frame() {

// pop the last frame off stack

let top_frame = self.stack.pop().unwrap();

// carry over return pointer so the callee

// ultimately returns to the right place

callee_frame.rp = top_frame.rp;

}

// push the new frame onto stack

self.stack.push(callee_frame);

}

// ...

}

This method of stack replacement isn’t zero-overhead – the VM still incurs a cost for checking for tail calls at runtime at every function call site – but it’s much lower overhead that wrapping every return value in a Thunk struct like in the Go-based interpreter. This extra degree of control is the benefit of controlling Ink’s call stack explicitly in the VM, rather than relying on the host language (Go)’s call stack.

The September compiler

Unlike the other two environments, where we were interpreting Ink code in a runtime we controlled, the September compiler has a different goal: transform Ink code into equivalent JavaScript that runs elsewhere in Node.js or a browser. This means we can’t do funky stack reuse tricks or use thunks everywhere, but it does allow us to rewrite certain parts of our Ink program. This rewrite process is how September supports TCE.

The first option I considered was a full source code transformation technique, the way ClojureScript transforms recur tail recursive calls to while (true) loops. This is probably the ideal solution, but I got stuck in implementation, so decided to take a slightly easier approach: selectively injected trampolines.

A normal tail recursion trampoline has a few undesirable downsides:

- It changes the original tail recursive function incompatibly, by changing its return type to sometimes be a trampoline value (thunk)

- It adds unnecessary overhead to all function calls, if all functions are trampolined

September’s compiler implements a selective trampoline to support tail call optimization, by detecting cases of self tail-recursion – when a function tail-calls itself – and transforming only those function calls into trampoline calls. It also adds a special construction inside these transformed functions so the trampoline is contained, and the overall return type of the function isn’t changed. This overcomes the two main problems with trampolines. Although this isn’t completely reliable TCE because it can’t support all tail calls, it supports the use cases that matter.

As an example, here’s the simplest possible tail-recursive Ink function. It loops by counting down from the given n until zero, and returns 'done!'.

countDown := n => n :: {

0 -> 'done!'

_ -> countDown(n - 1)

}

log(countDown(10))

Compiling with september translate countDown.ink transforms this Ink code to the following JavaScript.

countDown = n => (() => {

let __ink_trampolined_countDown = n =>

__ink_match(n, [

[() => 0, () => __Ink_String(`done!`)],

[

() => __Ink_Empty,

() => __ink_trampoline(__ink_trampolined_countDown, n - 1),

],

]);

return __ink_resolve_trampoline(__ink_trampolined_countDown, n);

})();

log(countDown(10));

There’s a lot more code here to support the trampoline, but the key to this transformation is that Ink has created a new function for us inside our countDown function called __ink_trampolined_countDown. This is a version of countDown that returns a trampoline value (__ink_trampoline(...)). The overall countDown function returns the value you get when you call this trampolined function with the trampoline unwrapped. We can see this at

return __ink_resolve_trampoline(__ink_trampolined_countDown, n);

The end result is that we’ve created a trampoline for countDown to implement TCO for this function, without changing the return type for countDown itself because we’ve hidden the actual trampoline completely within the function.

There are downsides to this approach of TCO taken by the September compiler. Most importantly, this kind of code transformation only works for cases of clear self-recursion. If you’ve renamed your recursive function, or if you have mutual recursion or something more complex, the compiler won’t be able to recognize tail recursion and perform the correct transformation. I think this is a worthy tradeoff in ergonomics for a big benefit: painless tail call optimization where it matters most, in loops and iteration.

Conclusion

At its core, tail call elimination is a powerful construct that lets us express infinities. It lets us say “this value is defined as the result of this infinite calculation” without actually performing an infinite amount of work right away. For Ink, this gives us an elegant way to express many iterative algorithms. There’s a whole microcosm of research concerning efficiently performing tail call elimination or optimization in various environments, and we’ve seen some of them here. Like any technical choice, the techniques come with a variety of tradeoffs between runtime and compile-time performance, simplicity, and compatibility.

I think it’s pretty cool that even between the three different Ink implementations, tail calls are implemented differently due to the different constraints in their respective environments. Sadly, it seems like there’s a shortage of accessible material online about how different production languages implement TCE in general. But hopefully this serves as a worthwhile contribution to that small collection.

← Implementing the lambda calculus in Ink

Assembler in Ink, Part I: processes, assembly, and ELF files →